Jeffrey D. Wilhelm

Which one of our children is expendable? Whose needs can we afford not to meet?

Which injustice in the world, what pressing environmental problems can we choose to ignore?

Since the answer to both questions is obviously: none at all, then what we, as individual teachers and citizens (who are always informally teaching), can do today for learners, let us do today. What we can then do tomorrow, let us do tomorrow. What control we have, let us exercise it fully. Certainly, there is much to do.

Teaching for transformation

Transformational teaching is the kind of teaching that transforms a learner’s perspective, understanding, capacity and activity in the world. Transformational teaching works for social and environmental justice, and works to actualize our best possible selves and our best possible communities. It works for transformed ways of being and of acting that are for the benefit of all.

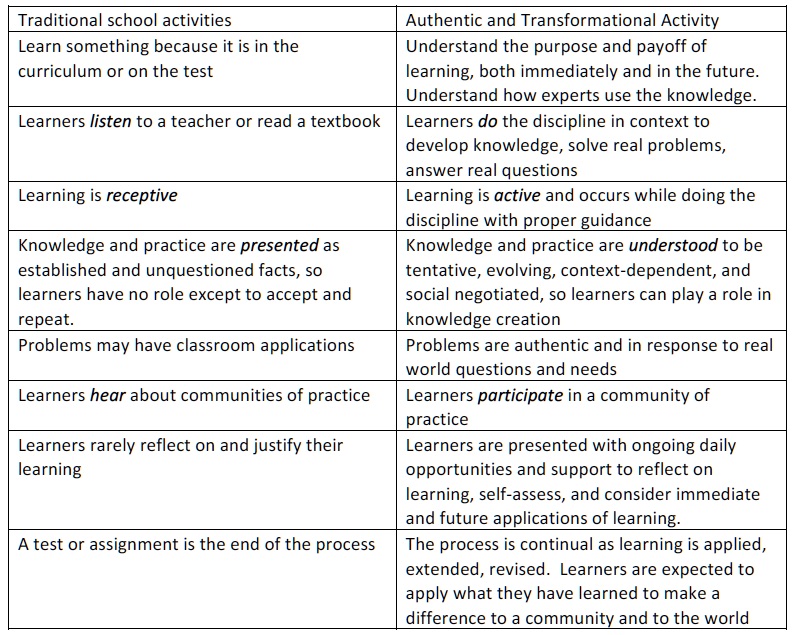

Despite the best of intentions, there is a gap between what is known about transformational teaching and what we do. Part of the problem is the old Donald Rumsfeld dilemma: we don’t know what we don’t know. Often, teachers are not aware of the consensus understandings from cognitive science, educational research, human development and other fields, so they don’t know how to put these insights into practice. Another part of the problem is that even when we do know the research and best practices, we often suffer from what is called the “knowing-doing gap”. Research shows that teachers tend to default back to traditional informational forms of teaching.

Traditional teaching is invited by many traditional school structures and expectations. So even when we do know what to do, we often don’t do it as individuals or as systems (see, e.g. Zeichner & Tabachik, 1981; Bryk, et al 2016). Teachers who think they are making the necessary shifts may not be doing so or doing so consistently. This second problem is a bit like knowing you should floss your teeth every day, or that you should start off your day with some guided meditation. We know we should do it, but we often don’t for various reasons.

Making these shifts to transformational teaching could not be more important. Significant political and environmental challenges are already here. More significant ones are coming and our educational practices are not yet meeting the demands of the present moment nor the future. Many of the problems our students must deal with are still evolving, and many of our most pressing current problems do not yet have solutions. Social agreements about knowledge are constantly changing. Did you notice that Pluto is no longer a planet? And the job market is rapidly changing too. The World Economic Forum estimates that over 2/3rds of today’s kindergarteners will enter fields that do not yet exist. Studies by Autor, Levy and Murnane (2003) and Autor and Price (2013) explore the changing demand for skills in the US workplace. The only jobs that are growing – and they are growing exponentially—are non-routine analytical and non-routine interactive. Routine jobs that do not require creative communication, analysis and on-the-spot problem solving are all but disappearing. In other words, our learners need to learn how to learn, how to relate, and how to collaborate to solve new problems and create new knowledge. What good is information in a world like this?

Here’s the gist. The way schools (especially American ones) traditionally

—and typically still—teach kids does not suffice to meet the demands of next generation standards and assessments, nor does it meet the demands for real world expertise, for learning how to continuously learn and improve, nor for learning how to meet new challenges, nor for how to transform the self, community and world. As various studies show (e.g. Newmann, et al, 2016; TNTP, 2018), authoritative and informational teaching practices still dominate American teaching. This kind of teaching hurts all learners, but those learners who are minorities, living in poverty, or marginalized in any way are especially at risk. The loss of human potential and life satisfaction is nothing short of devastating.

Nearly 50% of American high school dropouts reveal that they left school because it was not interesting nor authentic, and 70% disclose that they were neither motivated nor assisted to work hard by typical school assignments and structures (Bridgeland, DiIulio & Morrison, 2006). In contrast, we have found that nearly all learners, especially students who often struggle or are considered at-risk enthusiastically embrace guided inquiry/ICA approaches (Smith & Wilhelm, 2002, 2006). Schooling suddenly makes sense, is purposeful and usable, is culturally relevant, promotes competence and personal power, and students get the help they need at the point of need.

Of course, we all want our human activity and teaching to matter right now and to make the biggest difference possible through the future. This requires a momentous shift away from traditional teaching practices: moving from providing information to teaching for transformation; moving away from lecturing, reading textbooks and teacher led discussions and towards collaborative inquiry and apprenticeship into expert practice. The positive impact of a such a shift is incalculable.

In many studies (see, e.g., Smith and Wilhelm, 2002; 2006), learners have been found to crave personally engaging, challenging, and socially significant work. Our youth WANT to be transformed; they want to work for social and environmental transformations; they want to be of service to others and the world. The problem does not lie with students. Yet the quality of learners’ lived through experience in school has been shown to be dire. School, particularly the academic experience, can be mind-numbing. As all of us can attest from personal experience, such a situation does not promote motivation or learning. A current emphasis on standardized testing has only exacerbated the problem. But most heartbreaking to me is how easily, even in the face of existing constraints, the experience of learning could be different, and learning in school could be significant, engaging, and fun. This will only happen if teachers take the necessary steps through the crossroads in their own classrooms. We must also take steps forward in our own schools, communities, and professional networks. The steps forward are under our control to take. To this end, I propose six steps all of us, as formal or informal teachers and citizens, can take right now.

1: Take responsibility for whatever is under our control.

We must not let ourselves off the hook. We know that the most important factor that affects and improves student learning and their application of that learning is quality teaching (See, e.g., National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future, 1996).

There are two distinct areas where important decisions about education are made. The first and foremost is in the classroom, made by teachers. Let’s make the decisions open to us and make them in the most wide-awake way possible, based on what we know, both from research and our reflective practice, will best benefit our own students

The other area is in the policy arena, where decisions are made by elected officials or appointed leaders. These decisions have an undeniable effect, but they do not keep teachers and community members from enacting motivating and appropriately challenging learning activities with others. We must not use policies as an excuse not to do so.

2: Rethink teaching as a personal and relational pursuit.

Many teachers I know profess to teach students; some argue that they teach content. In fact, as George Hillocks (1995) eloquently argues, teaching is a transitive verb. It requires a direct and an indirect object. We teach something to somebody. If we forget the something, and even worse, the somebody—those specific human beings in our classrooms—we miss the joy and power and very purpose of teaching. And we will certainly accomplish very little. As we teach content to students, we must relate to them as human beings in all their complexity, and we must help them to relate to the wonder and magic of literature, composing, science, history and math, and we must encourage them in turn to relate what they are learning to the world. Teaching and learning are fundamentally relational pursuits. The major danger of standardized curricula and tests, in my opinion, is that they distract our attention away from our students as human beings, and away from the wonder, fun and power of reading, writing and learning as meaning-making pursuits that can stake your identity and do amazing and transformational kinds of work out in the world.

3: Reframe language arts—and other subjects too—as personal studies and inquiries.

Some commentators have wondered (e.g. Bizzell, 1994; Pratt, 1990) whether English language arts is in fact a discipline at all. It was inserted into school curricula rather late in the day, by Matthew Arnold in Great Britain towards the end of the 19th Century. It does not have a community of practice outside academe, but is instead what other disciplines use to do their own work. Nonetheless, I would argue that English language arts are a vital and unique part of educational experience because language arts is the most natural place to explore personal and social issues of the most compelling nature. By reframing ELA as personal studies (an idea promoted by my friend and colleague Bruce Novak) into essential personal and socially significant issues, we could free ourselves from what I consider to be schoolishly narrow definitions of literature and too much emphasis on correctness and objectivity in writing. Instead, such a reframing would encourage us to vitally connect learners to texts and ideas that meet their needs to explore and extend their thoughts and feelings about important issues, and to write with voice and vigor as they explore and express their thinking to themselves and to others, and begin to rehearse how to use such learning to work for real world transformations.

I recently completed a study on how students engage with texts that are not typically valued or used in school, such as video games, manga, horror, etc. Astonishingly, many very adept readers cannot identify a single engaging or meaningful text that they have read in school. I don’t care how well these students read, or how many personally enriching texts they read outside of school—these students are underserved by school. I would argue that any student who does not engage in meaningful activity, read stimulating texts, and write/compose something of interest and use to them each and every day in school is in fact being underserved. A focus on ELA as personal studies and inquiries can help us to focus on these kinds of stimulating experiences that are at the heart of learning.

A focus on personal studies and inquiries can help any learning experience be applied to the world to make transformational change.

4: Talk with others about improving educational experiences and focus on literacy

as you do.

Schools have a PR problem. And I suggest that we need to be proactive versus reactive in dealing with issues that affect teachers and students. If we do not speak, then not only are we voiceless, but so are our students. We need to take on the role of Dr. Seuss’s Lorax for our kids. We need to proactively discuss reforming or just plain improving the educational experience with parents, colleagues, administrators and policy makers. We can do this through simple conversations, forums, teacher research presentations, op-ed pieces, or writing and even testifying to our legislators. As John Milton asserted, truth was never bested by a bad argument, lest the arguments were not made. We need to be part of the conversations that affect us. We need to keep crucial issues on the table. As we know from history and America’s own founding father George Washington, you don’t have to win many battles to win the war. But we do have to keep the issues alive. In America, 75% of citizens do not have a current personal connection to school. This makes them at best disinterested in educational issues. We need them to understand that the education of our children does deeply and personally affect them and show them how. We can only do this through conversation. And conversation, as John Dewey asserts, is democracy. As we engage in such conversations, I suggest we talk about literacy. Literacy is something I believe everyone can value and support, that is important to daily life, all areas of work, and in all subject areas. Improving literacy is a starting point we can all agree upon. Literacy is also essential to developing capacity and power, to conversing, and to making transformative change in the world.

5. Work to reframe all content area curricula as problem-oriented inquiries.

(Wilhelm, 2007)

To connect students to the energy, passion and purpose of the subject areas, work with colleagues to reframe what they teach with essential questions. Reframing a biology unit on life cycles with “Who will survive?” or a nutrition unit on food with “How does what we eat and how it is produced affect us and the environment?” reconnects students to the purposes of learning disciplinary concepts, and engages them in learning the processes of doing the discipline. They will become more competent at doing the discipline instead of just learning for school. Since literacy is implicated in all disciplinary inquiry, work to help colleagues see how to help kids read more like expert practitioners in math or history, and collect data, think and compose more like experts too. Because reading and writing particular texts, like arguments, lab reports or data tables, is different in various disciplines, we must all become teachers of literacy. Learning to read and write like a historian or scientist will help learners to engage with the subject as subjects who engage, read, write, problem-solve, learn and stake claims for themselves based on expert thinking and available data.

6. Use interactive strategies that meet learners’ current needs for personal relevance,

and socialas well as disciplinary significance—and that develop and use social imagination.

Many studies show the importance of using engaging, interactive, hands-on techniques for developing new processes of meaning-making and deep conceptual understanding (see, e.g. Wilhelm, 2002, 2007, 2008). I would also make the case for the importance of developing and using social imagination. Social imagination is essential to all learning. We must be able to imagine what it was like to live in a different time or place, to imagine what might happen if we extrapolate data patterns, to imagine a story world or a mental model of how feudalism would affect us or how inertia works. Most importantly, perhaps, we must be able to imagine ourselves as the kind of person who would want and be able to use what is being learned when we are out in the real world, and we must imagine ourselves doing so. We must be able to imagine making a difference through who we are and what we are learning to become.

One technique that works towards all these ends is drama. Drama and visualization strategies that support social imagination (as well as supporting many other reading, composing and problem-solving strategies) are among the most underused and powerful techniques in our teaching repertoires.

To look at just a few features of drama strategies (or action strategies, Wilhelm, 2008, 2012): they put teachers in the role of facilitating student activity and student understanding. They help reframe instruction as these strategies foreground students’ current state of being, their interests, and their engagement but moves them towards new and deeper understandings. Drama provides an imaginative rehearsal for living through problems and is a form of inquiry and problem-oriented play.

Drama fosters different kinds of classroom interactions since we can speak as someone else and give voice to silenced perspectives. Drama foregrounds our personal human connections to studied material. Drama helps students to give personal voice to universal issues.

But whether you use drama or not, the point is to continually experiment with and reflect on the use of various techniques for the purpose of improving our students’ educational experience. This, after all, is the life work of a teacher, and worthy work it is.

In your class—or in your own community situation – at this moment, many of your students, thinking partners, fellow citizens, informal co-learners, et al may have their last best chance to engage, learn and succeed, to become readers, to begin actualizing their potential, to work for transformation. Reach out. Grasp the moment. Pursue it. With urgency.

Postscript: When I Met Johanna Rolshoven

The most formative experience of my life was a year I spent as a Rotary Scholar in Saarbrücken Germany in 1980-81. I had the great good fortune to live with the Rolshoven family. This is how I met “meine Schwesterchen” Johanna. Hanna was a revelation to me. I’d grown up in a fairly conservative home and was not all that aware of how all human activity is political. I was mostly oblivious to the state of the world and my potential role in reinforcing or changing it. Hanna eagerly and patiently became my tutor in such matters, at her home, on long drives to Marburg, and in other venues. Hanna gave me an “Atomkraft, Nein!” pin to wear, with the message emblazoned across a yellow smiley sun pin. She took me to a Stopp Strauss! rally at the French-German Friendship Garden. Hanna also gave me many other gifts– a small handcrafted wooden bookshelf which I still treasure—and her patient friendship—which I treasure even more, beyond measure. From such time I count my political awakening and my journey as a teacher. In the preceding chapter, dedicated to Hanna, I trace some of my current thinking as a teacher, and as a teacher of teachers, in the English language arts in current day America.

I think and hope that the message is one that can be compelling to anyone who teaches any subject, whether formally or informally, in an official capacity or informally as a citizen and thinking partner with others. I offer it here as a gift to Hanna on her birthday, but also to any reader who chooses to peruse it.

Works Cited

Autor, David H., Frank Levy, and Richard J. Murnane. 2003. ‘The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration,’ The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), pp. 1279-1333.

Autor, David H., and Brendan Price. 2013. The Changing Task Composition of the US Labor Market: An Update of Autor, Levy, and Murnane (2003), June 21, 2013, MIT economics <https://economics.mit.edu/files/9758> [PDF], [accessed 2018-12-24]

Bryk, Anthony S., Louis Gomez, Alicia Grunow, and Paul LeMahieu. 2017. Learning to Improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Publishing).

Bizzell, Patricia. 1994. ‘Contact Zones and English Studies,’ College English 56(2), pp. 162-169.

Bridgeland, John M., John J. DiIulio, and Karne Burke Morison. 2006. The Silent Epidemic: Perspectives of High School Dropouts (Washington DC: Civic Enterprises).

Hillocks, George. 1995. Teaching Writing as Reflective Practice (New York: Teachers College Press).

National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future. 1996. What Matters Most: Teaching for America’s Future: Fostering High Performance and Respectability (TEACHINGpoint/Waterpress), <http://www.teaching-point.net> [accessed 2019-04-07]

Newmann, Fred M., Dana Carmichael, and M. Bruce King. 2016. Authentic Intellectual Work (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin).

The New Teacher Project. 2018. The Opportunity Myth. What Students Can Show Us About How School Is Letting Them Down – and How to Fix It (TNTP.org), <https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf> [accessed 2019-03-03]

Pratt, Mary Louise. 1990. ‘Arts of the contact zone,’ in Ways of reading (New York: Bedford Books), edited by David Bartholomae and Anthony Petrosky, pp. 528-542.

Smith, Michael W., and Jeffrey D. Wilhelm. 2008. ‘Reading don’t fix no Chevys:’ Literacy in the lives of young men (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann).

Smith, Michael W., and Jeffrey D. Wilhelm. 2006. Going with the Flow (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann).

Wilhelm, Jeffrey D. 2012. Action Strategies for deepening comprehension (New York: Scholastic).

Wilhelm, Jeffrey D. 2007. Engaging Readers and Writers with Inquiry (New York: Scholastic).

Wilhelm, Jeffrey D. 20013. You Gotta BE the Book (New York: Teachers College Press).

Wilhelm, Jeffrey D., and Michael W. Smith, M. 2014. Reading Unbound: Why kids need to read what they want and why we should let them (New York: Scholastic).

World Economic Forum. 2016. The Future of Jobs and Skills, Reports Chapter 1, <http://reports.weforum.org/future-of-jobs-2016/chapter-1-the-future-of-jobs-and-skills> [accessed 2019-03-16]

Zeichner, Kenneth M., and Robert Tabachik. 1981. ‘Are the effects of university teacher education “washed out” by school experience?’, Journal of Teacher Education 32(3), pp. 7–11.