Elisabeth Luggauer

Fig. 1: Ćemovsko Polje, view towards Vrela Ribnička,16. 2. 2016. Picture: Author.

The „Dog Park“

“Musko ili žensko?”, that is to say “male or female?”, calls out a grey-haired man with a grey moustache, wearing a dark tracksuit, as my dog Ferdinand and his Belgian shepherd notice each other and approach one another in Pasji Park Rea (“dog park”). “Musko”, I respond, and the man does not seem to mind the approach of my male dog. After the dogs have approached each other, they smell each other, circle each other, their heads and tails are upright, their necks stiff. Behind the dogs, the man and I are getting closer to each other. Ferdinand and the female dog start to explore the surroundings together. They sniff the soil of low plants, gravel, red sand, they sniff at the bushes, trunks of pines of different ages, agility equipment made of blue and red wood and metal, benches and tables made of rustic wood, all positioned in the “dog park” (cf. research diary, February 28, 2016). On a sensory walk together with my dog Ferdinand through the Zmaj Jovina, one of the three main roads in the suburb Stari Aerodrom in Podgorica, I was told about Pasji Park Rea as a “forest for dogs” (šuma za pse). On the street corner in front of the Pavle Rovinski primary school, a man in black clothes, hidden behind an umbrella, stumbled across Ferdinand. In the few words we exchanged about his liking of Ferdinand, he noticed that I was a stranger in Stari Aerodrom, indeed. He asked if I have taken him for a walk in “šuma za pse” already. He points along the road in the direction of a large brownfield area which leads to Zmaj Jovina at its southern end (cf. research diary, February 12, 2016).

A few days later, in the late morning, Ferdinand and I crossed Bulevar Veljka Vlahovica at the end of Zmaj Jovina and took a walk along this green area on a beaten path. I had already looked for this “šuma za pse” the evening before and wanted to explore it again by daylight. To my left, the fallow is partly confined by a high metal fence, to my right by a long, flat building. Straight ahead, the surface ends in a horizon of conifers. In the sparse net of low green-brown, sometimes very prickly plants, which covers the ground between the many wider and narrower, red, clayey, muddy, stony, well-trodden paths, larger and smaller stones, parts of plastic, shards of glass in different colours, pieces of wood and metal, parts of furniture, scraps of cloth and faeces are interwoven. Plastic and paper scraps rustle in the light breeze. It is windy, cool and foggy. The ground is moist and sludgy and traversed by large puddles of heavy rainfall from the last few days. Various actors move across the surface in different modes of movement and at different paces.

Fig. 2: Ferdinand on Ćemovsko Polje, view towards the “magistrale”, 16. 2. 2016. Picture: Author.

Fig. 3: The matress of the “matress-dog”, 16. 2. 2016. Picture: Author.

Ferdinand and I seemed to be the only walkers in this space. A delicate, black dog’s head with pointed ears suddenly rises from a mattress that protrudes from the floor-covering mix of materials in an arrangement of several pieces of furniture. The dog jumps up from the mattress only a few meters away from Ferdinand and me. With her tail drawn in, she dodges a young man with a shepherd dog on a leash, approaches Ferdinand carefully and makes small jumping movements. Ferdinand accepts her request for a play. I observe them for a few minutes and proceed with my walk along the beaten paths towards the conifers. Ferdinand is following me.

An oval path of fine grey gravel runs through the coniferous trees, with fitness equipment set up at regular intervals along the edge. The gravelled path surrounds a children’s playground. I can smell the scent of moist soil and wet wood. After a few steps in the forest area, arranged in a circle between high pines, lower bushes and wooden tables and benches, I notice blue-red agility equipment, which is a sport where dogs have to master an obstacle course. Colourful wooden signs attached to the trees say “Badi”, “Ctark”, “Noa” and “Pasji Park Rea” (“dog park Rea”). This must be “šuma za pse”. Ferdinand and I walk around the park along the dog agility. Dust bins or outdoor gym equipment are attached to some tree trunks, a man is sitting on one of the benches, without a dog, reading a paper (cf. research diary, February 16, 2016). Back home, I was looking up the “Pasji Park Rea” on the internet and found blog entries reporting about the founding of this park in 2014 as the first park for leisure time with dogs in Montenegro (Kalać 2014).

Fig. 4: The “dog park” on Ćemovsko Polje, 16. 2. 2016. Picture: Author.

“Gehen in der Stadt”

In 2001, Johanna Rolshoven wrote the paper “Gehen in der Stadt” in a festschrift for Martin Scharfe. In the paper, she walks through Florence together with Justin Winkler and a group of students. The paper deals with “walking as a ‘means of transportation’ and as an individual form of expression”, it talks about walking as “an instrument of appropriation of space” and “ethnographic knowledge acquisition” (Rolshoven 2001 (2018), 13; translated by the author). My paper takes Johanna Rolshoven’s sensory walk through Florence as a model and explores Ćemovsko Polje (“Ćemovsko field”) on the southern edge of Podgorica (Montenegro). In my first perception, I categorized Ćemovsko Polje as an “urban fallow”, an area on the outskirts of the city that had been left to itself for little consideration and which was mainly used as a transit point and garbage dump. Repeated walking, running and driving on, through and in Ćemovsko Polje allowed me to understand this landscape-designated field, whose “fallow” land constitutes only a fraction of its extent, as an ethnographic research field and an urban space made by different actors. While Johanna focused herself on human “city walkers“ and their practices in Florence, my research experience also took into account both human and other than human “Ćemovsko-walkers”, who acquire Ćemovsko Polje not only by foot but also through running, driving, flying, etc.

From Place to Place

In “Gehen in der Stadt” Johanna Rolshoven wrote: “It matters where you start from, where you go from, where you go to. The starting point determines the modalities of the individual final account on a journey. The own standpoint – not just theoretically but also empirically – includes the realization of the expectation brought along with the passenger’s luggage. As the sum of one’s own gender- and milieu-specific as well as a nationally shaped relationship to certain places, it is always determined both individually and socially-historically” (2001, 11-12; translated by the author).

My biographical, milieu-specific, theoretical and empirical “luggage” of expectations has been packed in the south of Austria since the late 1980s. It was further expanded, from 2005 onwards, in the former Institute for Folklore and Cultural Anthropology in Graz, by the perspective of a city as “the sum of its inhabitants” (Rolshoven 2010, 23; translated by the author), which I became interested in thanks to the jubilarian. For my fieldwork, as a part of my dissertation project, I lived in an apartment in the attic of a single-family house in Zmaj Jovina in the district Stari Aerodrom in Podgorica from February to September 2016, in which I am – still – examining Podgorica as a sum of human beings and other city dwellers. In this project, I am specifically interested in the relationships between human city dwellers and stray dogs. What is it like to live in Podgorica next to stray dogs, which also occupy the urban space? How do both of these different groups acquire this urban space, negotiate it and how do they create the urban space Podgorica through their relations? During my fieldwork, I also had Ferdinand my then eight-year-old Slovakian mongrel dog from the animal shelter with me. His presence and everyday practices turned out to be tools for broadening my human perception in this research and at the same time a key to approaches of this very field of research between humans and dogs.

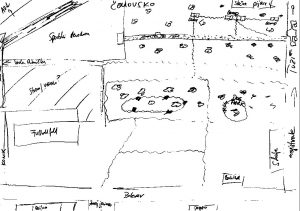

Fig. 5: mental map of Ćemovsko Polje, made by the author in august 2016.

Ćemovsko Polje

The previously searched “šuma za pse“ that actually turned out to be “Pasji Park Rea“ is located in one of the forest areas, which parallel crosses the whole area of Ćemovsko Polje. This “area” (Polje) connects to the last houses of the suburban quarter Stari Aerodrom in the south. Stari Aerodrom (old airport) was named after the near-by former military airbase that is used today as a hobby and sport airfield under the name “Sportski Aerodrom“. The first houses in this post-socialist suburb were built in the late 1980s (cf. research diary March 14, 2016; May 16, 2016) and function mainly as a residential area. Among the single-family houses, some of which have been left in the early stages of construction, there are larger and smaller residential buildings, supermarkets, kiosks, bakeries, bars, and restaurants. The demand for living space caused by the strong influx to Podgorica, especially from northern regions in Montenegro, also leads to a densification of the urban district in Stari Aerodrom. Fallow areas are constantly being transformed into cultivated living areas. Eastwards of Ćemovsko Polje abuts, on Vrela Ribnička, a district on the outskirts of town. In Vrela Ribnička there is the largest settlement of Romanies in Podgorica, the city dump and “Azil za pse“, the “dog shelter”. In the southeast, Ćemovsko Polje is bounded by the city’s cattle market “Stočna Pijaca“. In the south, the main street, which connects Podgorica and Tuzi, the last larger city to the border to Albania, divides the here described part of Ćemovsko Polje from its expansion as one of the “largest and most beautiful wine-growing districts of Europe” (cf. Plantaže 2019).

The Man in the “Dog Park”

Due to my quite limited knowledge of the Montenegrin language, I have to apologize to the bearded man in the “Pasji Park Rea” to slow down the incomprehensible and swift conversational gambit with the words “Izvinite, moj crnogorski nije tako dobro”. Thereupon, the man asks me much slower and more articulated: “Odakle si?”, where I am from. “Iz Austrije.” And what I am doing here in Podgorica? I tell him about my research about the coexistence of humans and stray dogs, and what a great coincidence it is that my apartment is right next to this park. The man told me, that he had mounted the park. My “Stvarno?”, that is to say “Really?” pretty much expresses all the incredulity, joy about coincidences and researcher’s luck I have felt at that moment. I introduce myself as Elisabeth, and ask him immediately if he could tell me something about it. He introduces himself as Rajko, points at his dog “Rea” and subsequently at the sign “Pasji Park Rea”, “dog park Rea”. If I were interested in stray dogs and whether I have seen the houses in the forest farther in the back already, he asks and explains that stray dogs are living there. He offers me to show them to me. Without knowing what he might mean with the stray dogs living in houses in the forest, Ferdinand and I join Rajko and Rea. We leave this forest area and cross another area covered with low, spiky plants. The green-brownish cover on the ground is again interwoven with various things. These plants are low; the area is also covered with shallow to deep holes, higher and lower hills out of furniture, garbage and bin bags, car tires and gravel. At the end, I can see a row of conifers again. Rajko attempts to guide me along the beaten paths. While we are walking, I try asking him questions about stray dogs. Are there many? Yes, that would be a problem as well, he replies. In Austria? No, that is why I am so interested in this topic. I see. “And that does not exist in Austria either, does it?”, he says and shoves a bin bag with his foot out of the way. I tell him, that I was surprised to hardly find any stray dogs in Croatia, but quite a lot in Bosnia. Of course, he says. They were brought from Croatia across the border to Bosnia and Montenegro; people were even paid for that.

We reach the conifer row. Rajko leads me through a clayey and uneven path through the forest area. I start to wonder where those houses could be. We cross a gravelled road and are again in a forest area. At one of the trees, I suddenly see a box-shaped extension. As we approach it, I recognize this extension as an improvised “doghouse”, as I had already seen it in Gorica, the inner-city recreation area. Bright, excited barking resounds from the hut. Two tiny heads, one white and one black are barking out of the tiny entrance. Rajko puts Rea on a leash and indicates that I should stop Ferdinand from touching the whelps. “Šuga”, he says, whatever this is supposed to be. Rajko’s worries seem to affect me and I call Ferdinand away from the huts. I ask, who has built these huts. “Drugarica”, a friend. He points towards a car stopping near us on the gravelled road. He strides up to it. He shouts something to the woman next to the car, who carries a whelp on her arm. She shouts back. I ask the young man, who is also standing next to the car, if he could speak English. “A little bit.” I hope that he would tell me more about the huts and dogs here. Indeed: more of these “camps” would be located here. They are occupied by dogs, which were found in the streets sick or injured and brought here. Meanwhile, the woman has put the light creme puppy down and has started feeding him and Ferdinand with single crumbs of kibble.

After the woman has put the light creme puppy back into one of the huts, she and the young men get back into the car and drive back to the main street. Rajko is about to go back. Since the dogs have “Šuga“, he explains again, it might be dangerous for Ferdinand. Is it dangerous for me as well? No, he laughs (cf. research diary, February 28, 2016).

In order to study urban cultures Robert Ezra Park already recommended research in movement as “nosing around” (Lindner, 1990). The encounter with Rajko, the conversation that resulted from it, and the joint walks through the unfamiliar research area that is part of his everyday life, transformed a sensory walk, that was guided by floating attention (Pétonnet 2003, 91-103), into participant observation and a go-along, according to Margarethe Kusenbach the company of an informant on his or her “‘natural’ outgoings” (Kusenbach 2003, 463).

Back in the “dog park”, we say goodbye and Rajko asks me if I have Facebook, telling me his profile name. From now on we meet more often, either appointed or by chance, for go-alongs on Ćemovsko Polje, which I don’t even know is called Ćemovsko Polje at this time. “A hybrid between participant observation and interviewing, go-alongs carry certain advantages when it comes to exploring the role of place in everyday lived experience,” elucidates Kusenbach the methodical importance of these go-alongs (2003, 463). Rajko works as a cameraman for the state TV station and lives with his son in an apartment in one of the high-rise buildings of Stari Aerodrom. He only has to cross the boulevard to be on Ćemovsko Polje. The care for “nature”, “water” and “air” is very important for Rajko and made him become a member of an NGO called OZON. When he moved to Podgorica a few years ago, he did not know where to take his dog for a walk. With a few like-minded people, he finally took a look at the fallow area opposite his house. Inspired and with the help of other committed dog owners, the forest area of this fallow was “cleared”, cleaned of waste and in collaboration with the city, supported by donations and NGOs, the “Pasji Park Rea” was created. This also involved the transformation of the rest of the forest area into a running track with gym machines and a children’s playground (Interview, April 26, 2016).

When spring 2016 turned more and more into summer, while we were walking together, Rajko often bent down to pick branches from the, for me indefinable soil-covering plant of plants, stones, shards and scraps of garbage and asked me, if I knew what it is. While walking with Rajko, I learned to recognize healing plants such as “kantarion” (amber) and “majčina dušica” (a sort of thyme) in the ground-covering plants and to name them in Montenegrin (cf. research diary, April 18, 2016).

With recourse to Klara Löffler and Elisabeth Fendl, Johanna Rolshoven reminds us in “Gehen in der Stadt” that we as researchers only see what we already know (Rolshoven 2001, 12). We can only rediscover what is already in our “luggage”. Knowledge about healing plants, for instance, was not in mine. Who knows what else I have not seen and what has not been pointed out to me through the eyes of other actors?

Fig. 6: Tamara in the “Camp”, January 2016, picture: NVO Ruka Šapi

The “Camp”

The day after Rajko showed me the “camps” on Ćemovsko Polje, I go back to take a closer look at them. Ferdinand is supposed to wait in the car for me so that he does not become infected with Šuga, which I have finally translate with scabies. Behind a dark car, I drive along the impassable gravelled road, which leads from the main street past the camps to the Sportski Aerodrom. At the height of one of the camps, where a woman is stirring in pots set up on the roof of the huts, the car stops in front of me. I ask the man, who just steps out of his dark vehicle if he took care of the dogs. No, but he needs to talk to “the girl”, who feeds them. They are both arguing loudly. On his way back to the car, the man tells me in a strict tone: “A lot of these dogs are aggressive. One day they will bite someone.” I now approach “the girl” and tell her about my research interest and that I would like to hear more about the dogs and her activities. She smiles in a friendly way and in a mixture of Montenegrin and very halting English, she starts telling me patiently that she is a volunteer in an organisation that takes care of stray dogs. This organization has established huts for injured or ill found dogs on the southern edge of Ćemovsko Polje. By turns, Tamara and other volunteers visit these camps regularly to feed and provide for the accommodated dogs. The huts of the camp, in which Tamara and I are standing now, are set

up in a row in a clearing. Built out of wood, stones, and card box in different heights, they are covered with plastic tarpaulin weighed down with stones. Due to the rain of the last few weeks, the earthy soil around the huts has been sodden. Tamara, the dogs and I are wading through the mud.

Fig. 7: “The Camp”, 12. 4. 2016. Picture: Author.

Fig. 8: Bubi and Štroko in front of the researcher’s car in the “camp”, 12. 4. 2016. Picture: Author

Fig. 9: “Borovi četnici“ on Čemovsko Polje, 13. 3. 2016. Picture: Author.

Scattered around the huts are coloured plastic bowls, empty cans of dog food, parts of furniture, car tyres and various white handkerchiefs. Tamara introduces the present dogs with their names and tells me how long they have been “in this camp”. She thoroughly shows me Štroko, a deformed, longish-small black and white dog with a gigantic head. She draws my attention to his forelegs, which are so bent that they have the shape of a heart. Since his friend Orka was gelded and is currently in Tamara’s apartment in the city centre to recover from her surgery, Štroko, she says, is very lonely at the moment. The dogs which jump up and down in front of me seem happy about our visit and the attention they get. The stern smell of wet dog and probably even some little faeces inhibits me from touching them. As we say our goodbyes, Tamara hands me her business card, stating her as a field salesperson for one of the largest importing firms in Montenegro. My clothing is covered in wet earthy-brown paw prints, the sleeves of my jacket smell of dogs, whereas Tamara’s black knee-high boots and her dark fancy coat look entirely clean, as she gets in her car with the label of the import firm on it. She turns, honks, and then skilfully manoeuvres the company car between the potholes, hills of bulky rubbish and boulders back onto the gravelled road (cf. research diary, March 1, 2016).

From this day on, I visited the camp more often.

Next to Tamara, I met Marina from the same animal welfare organisation that feed the ever-changing number of dogs in defined intervals. They also give them medication and take them to the veterinarians. The dogs were visited by other people as well. An old man from Stari Aerodrom visited a female dog regularly, which he called “my yellow one”. She lived next to his house, and after being pregnant, the neighbours have built a hut for her and her whelps (cf. research diary, March 9, 2016). Tamara told me in an interview that “the camp” has been started because of “this yellow dog”. She and the others also took care of the female dog, which lived around the old man’s house and which she called “Mama Živka“. When it became too precarious for the female dog and her whelps, they moved the house of “Mama Živka“ and her whelps onto Ćemovsko Polje, near the “dog parks “. Visitors of the dog park were not happy with the presence of “Mama Živka“ and her whelps, therefore the hut was moved farther back into the forest, where the camps were then established (cf. Interview, May 6, 2016; research diary, June 29, 2016; June 30, 2016).

Fig. 10: Orka, Zia and Bekica in front of the researcher’s house, 20. 8. 2016. Picture: Author.

The majority of pines that grow on Ćemovsko Polje are inhabited by processionary moths, as well as around the camps. In spring, “borovi četnici“, the caterpillars of the processionary moths, wriggle in meter-long, thin hairy snakes over the surface of Ćemovsko Polje. They can burn the mucosae of Ćemovsko-walkers to a necrotic histoid if they get into contact with them. In spring 2016, multiple dogs of the camp had to be treated due to cauterizations caused by the caterpillars. Henceforth, the female dog Zia has to live with half a tongue and a young whelp died from the consequences of this encounter (cf. research diary, April 13, 2016).

The camps, especially the row of huts that formed the centre of the camps, became popular whereabouts for me. I wrote many entries into my research diary sitting on a boulder in this camp with the laptop on my knees. Through my frequent presence in the camp I was able to talk to multiple camp visitors and pedestrians. The man I met, when I got to know Tamara, told me that he is working at Sportski Aerodrom and that customers were complaining about the dogs. They would be too aggressive, they would chase the cars, and someday, they would “probably bite someone”. I should take care of myself. Indeed, I was able to watch an incident in the course of which someone was chased. Every car that turned from the main street onto the gravelled road caused the sleeping dogs to raise their heads. Somehow, they managed to differentiate between cars that were escorted into the camps by them with wags of their tails, whimpering and happily barking, and those, which the dogs loudly barked at and chased along the gravelled path to the sport airfield, racing with a much too high velocity and cloaked in a dust cloud. To this very day, the claw marks on the quarter panels of my car recall the greetings of the camp-dogs. Eventually, I stopped the almost hysterical urge of showering and changing my clothes after every camp visit, learned how to protect Ferdinand against Šuga and therefore made him a regular visitor of the camp. Pulling ticks out of the camp-residents turned out to be a meditative activity to relax during my sometimes nerve-wracking fieldwork. During my stays in the camp, I learned more about the characters of the “main residents” of the camps, either by myself or together with volunteers. Orka, the large, black female dog, who got her name from Tamara because of the white rings that Demodex mites had formed around her eyes, appeared to be the leader. She was the largest, the strongest, always the first and the loudest. Or was it Bekica? A giant, snowy white female dog with a medium coat. Calm and deliberate, aloof, impressive. One of the two whelps, which lived in a hut as Rajko showed me, stayed in the camp. Her Šuga healed and she developed into a slender graceful white dog with brown markings and was named Zia. She was gentle and mostly of passive nature. Štroko, whose forelegs are bent to the shape of a heart, often annoyed me with his high-pitched bark and his pushiness, trying to demand contact. Suddenly, one morning in April 2016, a young light cream male dog was in the camp. Veterinarians diagnosed the constant twitching of his left forelegs, which often makes him lose his balance, as consequential damage of Štenećak, i.e. distemper. Despite Bubi’s difficulties to keep his balance, he could run amazingly fast.

Fig. 11: Tamara feeding “Ćemovsko” in their new location in the dog pension, 17. 6. 2017. Picture: Author.

During one of my first visits to the camp, a shepherd with his herd draws nearer to it. The sheep and the shepherd are welcomed by the barks of the dogs in the camp. Ferdinand joins in – a moment of going native? The shepherd silences the dogs with a firm “Neka”. He introduces himself as Ćajo and asks me what I am doing here. His sheep and those from a few other shepherds are housed in a flat building on the outskirts of Ćemovsko. During the day, he moves with them across Ćemovsko Polje. Currently, he has over one hundred of them. There would be little interest in the milk, none at all in the wool. The heaps of sheep’s wool scattered across Ćemovsko are the remains of the spring shearing of these sheep. Ćajo tells me that he loves dogs. He is accompanied by a mongrel female dog, which resembles a German Shepherd Dog. He also once had a Kangal Shepherd Dog to tend the sheep, but he became too dangerous and aggressive (cf. research diary, March 9, 2016; May 24, 2016).

As I left the house on the morning of April 15, 2016, I recognized Orka who was trotting on the fallow area opposite my house. She appeared to recognize me and ran up to me. Since that day, her visit to my neighbourhood has established itself almost as a daily ritual during my fieldwork. At first, she was solely accompanied by Štroko, soon after, also by Zia, Bubi, and Bekica. Thus, the dogs left the immediate surroundings of the camp. Along the way, they were seen in the “dog park” several times and finally moved in the direction of Stari Aerodrom. I could observe, how this small group moved along the trails from “Pasji Park” to Zmaj Jovina, while chivvying the cars, searching for food in rubbish, and finally resting under the lime tree in front of my house (cf. research diary, April 15, 2016; April 17, 2016; April 29, 2016; April 30, 2016; May 5, 2016; June 19, 2016). Henceforth, Tamara and Marina changed their routes from the city centre to Ćemovsko so that they could drive through Zmaj Jovina to gather up the dogs from under the lime tree. Tamara asked me to drive the dogs back to the camp if I notice them in front of my house. The five dogs always jumped into my tiny Ford Fiesta willingly and stuck their heads out of the open window while I was driving them back.

Štroko was adopted in the summer of 2016 and has been living with a family in an apartment in Podgorica since then. In February 2017, Tamara informed me that Zia died because she ate some poison that had been laid out near the camp. In March 2017, Orka died from eaten chemicals in the camp as well. Thereupon, Tamara, Marina and the other members of the organisation cleared the camp. Even though the dogs are placed in a kennel on the other side of the town nowadays, Tamara and Marina still call this group “Ćemovsko” when they speak of those dogs. They continue to provide for “Ćemovsko” regularly at their new location.

Fig. 12: Ferdinand and Peppo walking on Ćemovsko Polje, view towards Vrela Ribnička, 18. 3. 2016. Picture: Author.

Peppo

On March 2, 2016, a small, black-brown-white dog with whom Ferdinand had played a few days before in the “Pasji Park”, accompanied me and Ferdinand on our walks on Ćemovsko Polje. He appeared to move around Ćemovsko Polje without a human companion. He showed little interest in me but did not leave Ferdinand’s side anymore. He moved around with us through the dog park, along the open area between a belt of trees, when he suddenly became frightened of something and galloped back towards the houses in Stari Aerodrom. From that day on, the little one joined us more often. Sometimes, I had the impression that he would “lurk” somewhere on Ćemovsko, since he often came out of nowhere and appeared right behind us. Rajko and the other Ćemovsko-walkers told me that he had been living around a grey house in the row of houses at the most southern part of Stari Aerodrom and had been fed by Rajko and others. When Rea was on heat, Rajko told me, that he had slept in front of Rajko’s house for two weeks and never left Rea’s side on Ćemovsko. From April onwards, the little one, whom I named Peppo, attached himself to me and Ferdinand on almost all of my reconnaissance on Ćemovsko. The human visitors labelled him as “lutalice”. His presence in the “dog park”, a space, which has been created for human beings with “kućni psi” or “vlasnički psi” (“dogs of house” or “dogs of an owner”) to spend their free time together, irritated some of them consistently. I have been warned, that he, as a “lutalice“, could transmit diseases to Ferdinand. Even when Peppo had been examined by a veterinarian, turned out to be completely healthy and had now been vaccinated, the distrust against him was still there. There would be diseases that could not be diagnosed. Furthermore “lutalice” would be immune to diseases, which could be harmful to “kućni psi” or “vlasnički psi” (cf. research diary, March 2, 2016; April 18, 2016; May 11, 2016).

Fig. 13: Čajo, sheeps, and other walkers on Ćemovsko Polje, 17. 6. 2017. Picture: Author.

Designing Ćemovsko

Human beings walk and run around Ćemovsko in as flâneurs and sportingly determined. Some are accompanied by dogs who do not always adapt to the human pace. Ćemovsko Polje starts at Rajko‘s doorstep. He knows the different plant- and bird species on Ćemovsko. Together with Rea he always walks differently, sometimes determined, sometimes strolling and reconnoitring. Cars move at walking speed over the uneven ground of Ćemovsko, over the growth of aculeate plants, shards and refuse. The drivers of these cars sometimes stop in front of the forest area, which has been turned into a recreational area and walk or run along the gravelled track or park the cars in a hidden spot to spend some time alone or in company. As the shortest route from Vrela Ribnička to the city centre, Rom and Romni cross Ćemovsko purposefully along the wider well-trodden paths, either afoot, on bicycles, freight bicycles or on horse-drawn vehicles. Large, heavy off-road vehicles speed along the gravelled road back and forth from the main street to the sport airfield. It is Ćajo’s work to cross Ćemovsko with his sheep. He moves around slowly, abides repeatedly, and reverses to collect sheep that are left behind. Particularly on hot days, he moves around even slower with his plaid shirt wrapped around his head. The sheep trot as a herd, they move around as an inertial mass maid [made?] of grown-up sheep and lambs. Only barking dogs cause them to make a few hectic jumps sometimes. Many of the sheep walk with a limp. Ćajo reckons that the uneven ground is the cause of this (cf. research diary, May 24, 2016). Horses move to graze around Ćemovsko. They belong to the “Cigani” as my landlord and a neighbour explained. They could move freely from Vrela Ribnička on, provided they are not used to drag vehicles. The man, who has told me about “šuma za pse“, also mentioned that the horses would sometimes almost go as far as the city centre (cf. research diary, May 24, 2016).

The caterpillars of the procession moth wind their way in meter-long chains over Ćemovsko. They leave deep wounds when their line overlaps with the lines of appropriation of other actors. Orka, Štroko, Bekica, Bubi and Zia explore Ćemovsko walking, running and barking. Their habitat becomes a transit space on their way to Stari Aerodrom. Their practices of appropriation are driven by curiosity, tediousness or animal instincts and intersect with the practices of the targeted placement of chemicals or acid-immersed meat waste from the livestock market in the nearby forest area (cf. research diary, April 17, 2017). These negotiations of different forms of usages claimed Zia’s and Orka’s lives and turned the camp into a place of remembrance.

Johanna Rolshoven and I walked through Florence and Ćemovsko Polje as urban spaces. Our walking aimed at understanding these spaces as lived spaces. A cultural-anthropological awareness of spaces considers them as products of practices of appopriation and negotiation. Drawing on Michel de Certeau’s Kunst des Handelns Johanna Rolshoven conceptualised in “Gehen in der Stadt” spaces as created while manifesting them (cf. Rolshoven 2001, 15). With Otto Friedrich Bollnow’s Mensch und Raum she states that the lived space is created through paths that are walked and those walked paths follow a “relationship to the world designed from within” (quoted in Rolshoven 2001, 16-17; translated by the author). Then subsequently, I would like to summarise, that space and appropriation, as well as negotiation as practices, depend on each other. Spaces form practices and practices create spaces. Practices of space appropriation of human and other than human Ćemovsko-walkers, which establish Ćemovsko Polje as a lived space, occur as negotiations with the built and lived space encountered as the status quo of the appropriation practices of others. The space found through movement is always a snapshot in time, which is already appropriated at the moment of the uptake and thus changed and shaped accordingly. This action, found in a snapshot in time of other people’s practices is in turn determined by their “luggage”, which the appropriator and negotiator bring with her from her “relationship to the world designed from within” (quoted in Rolshoven 2001, 16-17; translated by the author).

In the first walk, Ćemovsko Polje presented itself to me as an area, that I tried to classify in, to me, generally known opposite categories: “designed green space” and “fallow land”. The refuse, the shards, and the faeces, which are interwoven with the ground-covering plants, gave me cause for concern that Ferdinand might injure his paws or that the water of the puddles might not be clean enough to drink from. Rajko not only sharpened my senses for the appearance and smells of healing herbs, but also made me understand that, a ground cover consisting of plants, shards, stones, refuse and faeces that triggers the feeling of “uncleanliness” to me, means a space for picking healing herbs he uses for his dinner to him. Walking and driving on Ćemovsko myself, I captured several human and other-than-human moving actors on Ćemovsko: Rom and Romni on bicycles, mopeds and horse-drawn vehicles moving purposefully and rapidly, human strollers who move along at a slow pace, relaxed and more hurried joggers or bikers, horses, shepherds, sheep, caterpillars, dogs alone or in company and actors who drive their cars to sports areas or hide in them in remote places. Initially, Ćemovsko Polje is a geographic description for a green area on the periphery of Podgorica. As a built, lived, remembered and narrated space, Ćemovsko Polje is the sum of appropriating and negotiating practices of human and other Ćemovsko-walkers.

References

Bollnow, Otto-Friedrich. 1990 (1963). Mensch und Raum (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer).

de Certeau, Michel. 1988 (1980). ‘Gehen in der Stadt’, in Kunst des Handelns (Berlin: Merve), by Michel de Certeau, pp. 179-208.

Fendl, Elisabeth, and Klara Löffler. 1993. ‘“Man sieht nur, was man weiß”. Zur Wahrnehmungskultur in Reiseführern’, in Tourismus-Kultur. Kultur-Tourismus, (Münster et al.: Lit), edited by Dieter Kramer and Ronald Lutz, pp. 55-77.

Kalać, Damira. 2014. ‘Dobrodošli u Park za pse “Rea”!’, in Ćemovsko Polje website, June 26, 2014. <https://cemovsko.wordpress.com/2014/06/26/park-za-pse-rea> [accessed March 3, 2019]

Kusenbach, Margarete. 2003. ‘Street Phenomenology. The Go-Along as ethnographic research tool’, Ethnography 4 (3), pp. 455-85.

Lindner, Rolf. 1990. Die Entdeckung der Stadtkultur (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp).

Pétonnet, Colette. 2003 (1982). ‘Die freischwebende Beobachtung. Das Beispiel eines Pariser Friedhofs’, in Hexen. Wiedergänger. Sans Papiers. Kulturtheoretische Reflexionen zu den Rändern des sozialen Raumes (Marburg: Jonas), edited by Johanna Rolshoven, translated by Justin Winkler, pp. 91-103.

Plantaže. n.d. Homepage der Weinbaufirma Plantaže (Crna Gora). <http://www.plantaze.com/about/vineyards> [accessed March 17, 2019].

Rolshoven, Johanna. 2010. ‘SOS: neue Regierungsweisen oder Save Our Souls – ein Hilferuf der Schönen Neuen Stadt’, in bricolage. Innsbrucker Zeitschrift für Europäische Ethnologie 6, pp. 23-35.

Rolshoven, Johanna. 2001. ‘Gehen in der Stadt’, in Volkskundliche Tableaus. Eine Festschrift für Martin Scharfe zum 65. Geburtstag von Weggefährten, Freunden und Schülern (Münster et al.: Waxmann), edited by Siegfried Becker et al., pp. 11-27.

Rolshoven, Johanna. 2017 (2001). ‘Gehen in der Stadt’, in ‘Gehen in der Stadt’. Ein Lesebuch zur Poetik und `Rhetorik des städtischen Gehens (Weimar: Jonas), edited and translated by Justin Winkler, pp. 95-111.