Michael Zinganel and Michael Hieslmair

Nodes and knots of transnational mobilities

With the transport volume of goods and people expanding, more and more people driving vehicles or being driven are obliged to spend increasing amounts of time in transit. Then both the (transnational) streetscape and vehicles become places of everyday encounter and experience. And places where, for various reasons, the flow of traffic stops or is interrupted, become operationalized as important sites for dwelling-in-transit (rather than as generic non-places): bus terminals, ferry ports, logistics distribution centers, formal and informal markets, or border crossing stations along the corridors. Of special interest in this context are highway service stations, because they are addressing a wide variety of mobile people travelling with different motives, rhythms and types of vehicles, while also (less mobile) locals try to participate in interactions with them.

These highway service stations are places to be inhabited for short periods of a break, overnight or sometimes even for weekends. Here trade might happen, rituals and routines of relaxation are developed, contacts initiated with regions of origin or target. This is also where those who were mobile before engage in cultivating and maintaining on-the-spot, fragmented communities. Here we can observe a “vernacular cosmopolitanism”1 and “doing with space” becomes a kind of “knotting”.2

By describing driving as a social practice and the motorway as a place always in a state of becoming, Peter Merriman brilliantly deconstructed Marc Augé’s notion of non-places,3 still largely prevalent in the field of art and architecture. Samuel Austin juxtaposes Augè’s negative perception, with similar ideas of highway stations as decentered, interrelated places of process, blurring the distinctions of local and global, place and non-place.4 During pauses in truck drivers’ auto-motion, Nicki Gregson argues, the space of the cab, made economic through driving the logistic network of supply chain capitalism, is morphed into a cozy and habitable space for dwelling in transit, a home-from-home.5

At a highway service station the large numbers of trucks, couches, mini busses, and cars constantly arriving and leaving might comprise a much larger volume of physical space than the solid buildings of a single gas station and restaurant. At these nodes, it seems, human forms of mobility are inseparably linked with non-human and immaterial forms. Thus, expanding arguments of actor-network theory (ANT), John Law famously introduced the different levels of scale of a network, starting with the description of a historic Portuguese vessel as an example, with “hull, spars, sails, stays, stores, rudder, crew, water, winds, all of these (and many others) have to hold in place functionally if we are to be able to point to an object and call it a (properly working) ship,” — and ending on a larger scale, with the Portuguese imperial system as a whole, with its ports, vessels, military dispositions, markets, and merchants.6 Accordingly, all single trucks, coaches, and transporter vans driving the trans- and pan-European road corridors, built by inter-connecting political and economic powers, represent such a multi-level and multi-scale network. Furthermore, the nodes are networks, where several components are co-contributing to the physical, functional, and social production of space on site.

But a highway service station — like any logistics distribution centre —, must not be perceived as a single place, or at least not a place confined to a single building, but as a place-as-network, a distributed place, existing over miles of rails and roads,7 interconnected by the polyrhythmic flows of different kinds of mobile actors. Highway service stations, increasingly substituting urban functions, contribute to the production of suburban archipelagos in between traditional metropolitan areas.8 The continuous transformation of and at these transit spaces generates the development of a dynamic polycentric model of a multi-local (sub-)urbanity or “post-urbanity”9 whereby each archipelago represents only a single station on a route taken by individuals or objects in their vehicles.

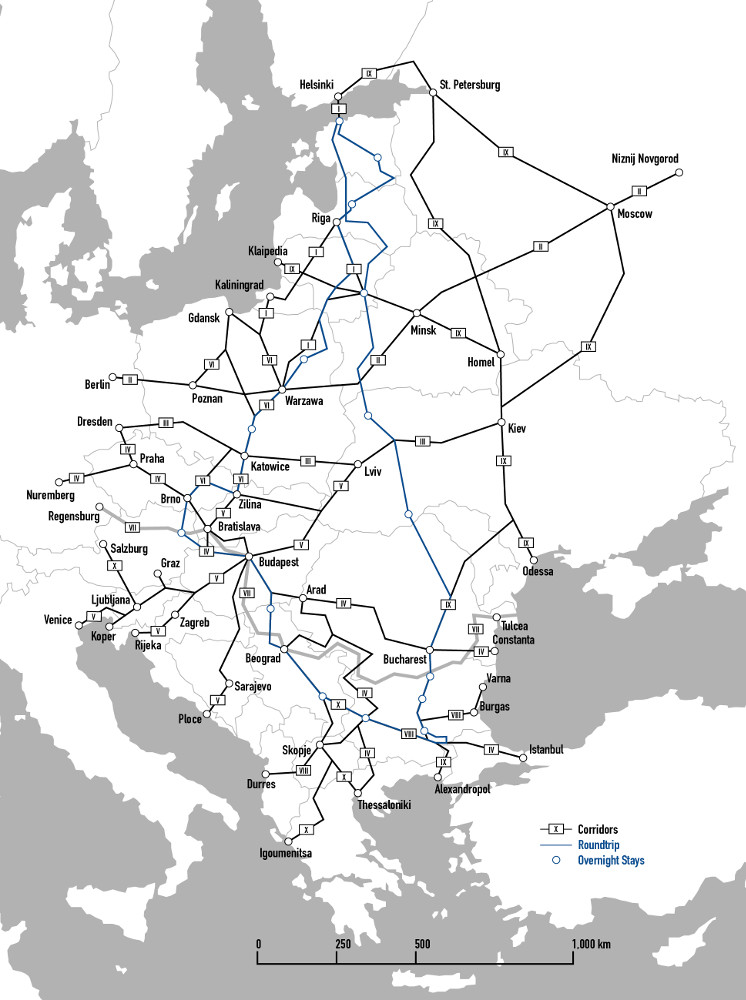

Mobilizing ourselves by the mobile lab: Austria – Estonia – Bulgaria

In a previous research project (2014-16) the authors were focussing on major pan-European road corridors, intended to network the former East and West of Europe in vital ways, re-constructed and modernized after the fall of communism and with the expansion of the European Union. We were interested in how people are ‘doing with space’ at such nodes and halts and what the transformation of road networks and road infrastructures are doing with/to people. Investigations of such networked places, constituted by polyrhythmic flows of people and vehicles, obviously also mean driving these routes and following the fluid characters from one stop to the next. In response to the call from Mobilities Studies protagonists for “mobile methods,”10 the authors therefore proposed a mobile ethnography enabling them to become physically immersed in mobile activities while simultaneously working on material and visual representations of networked mobilities:11

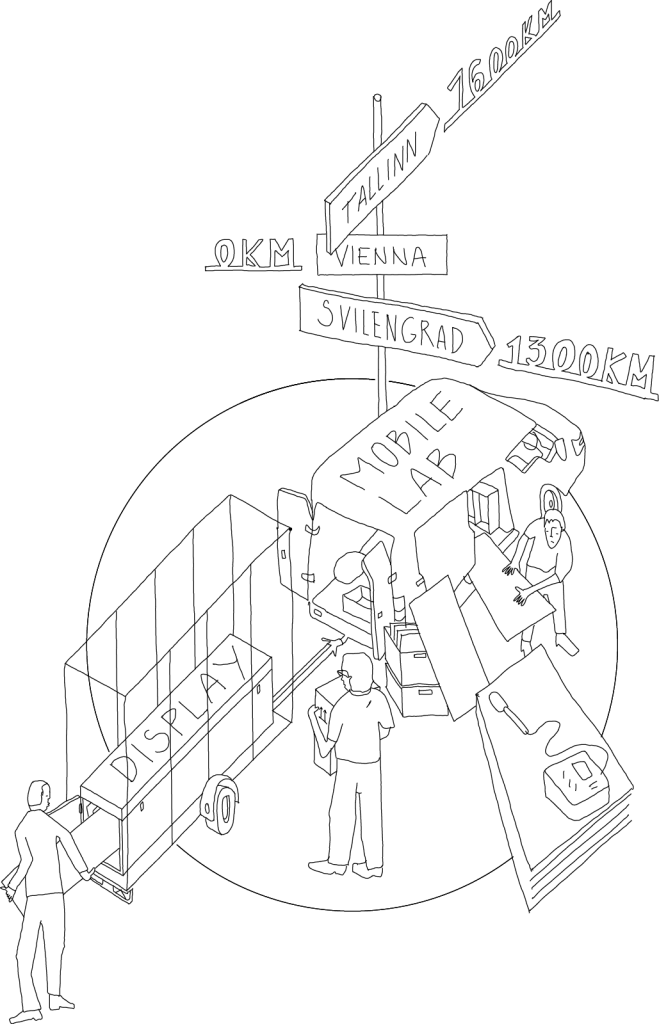

The core elements of investigation were to be intensive research trips along the geographic triangle of Vienna, Tallinn, and the Bulgarian-Turkish border. Hence, we wanted to rent a small van to pull a trailer that could be used both as a mobile toolbox and a fold-out display for producing large-scale mapping exercises in our projected field of research. However, we came to learn that there was no chance of renting any vehicle to drive to high-risk areas like the Baltic States, Romania, Serbia, or Bulgaria due to potential car theft. So we needed to purchase a second-hand vehicle ourselves. But after a desperate search we could not find any smaller car for a reasonable price, outside of a large Ford Transit transporter van.

This van also helped us to assimilate into the field of research: It looked like so many other vans driving the very same routes. And when waiting at one of the nodes, nothing helps you strike up a little conversation more easily than talking about your own experience with the vehicle itself, the items loaded, the workload of the driver, the route, the rhythm, the trouble with police and border controls, or the transport business in general. Transporter vans like ours are an attractive choice for professionals to escape the strict regulations and control mechanisms imposed on drivers of full-size trucks. They offer the opportunity to drive seven days a week around the clock and bypass the long waiting queues of border controls for heavy trucks to transport goods and people — with or without proper papers. Transporter vans of this type are the favorite vehicles for fitters and market vendors. Thus, we eventually decided to follow their routes from wholesale markets to open-air markets and vice versa.

But actually, we were also stopped to purchase road tax tickets close to each border station, to refill our gas tank every 650 kilometers at reliable-looking gas stations, to go to toilet, or to eat and drink what we considered “authentic” local or truck drivers’ food. We had some areas in mind where to stay overnight — but we wanted to keep the freedom of choice where exactly to stop. So each day, when the sun started to set we would go in search of cheap motels with parking lots, large enough to park our 14 meter long van and trailer combination. The more LGV trucks and vans like ours, the safer we felt protected against car theft and street robbery. But unlike truck drivers, we decided not to sleep in our van. Checking into motels, having a beer at night and breakfast in the morning seemed more promising for triggering additional chances for conversations and interactions with experts working at these nodes of transnational mobilities! To anticipate potential stops we traced our route on printed maps beforehand, attentively observed street side building types and signs, and stopped at gas stations with Wi-Fi access to google overnight accommodation we could reach before it got too dark. And — in case of emergency — we even asked a driver of another van with a regional number plate for advice, who personally guided us to the motel of a friend or cousin.

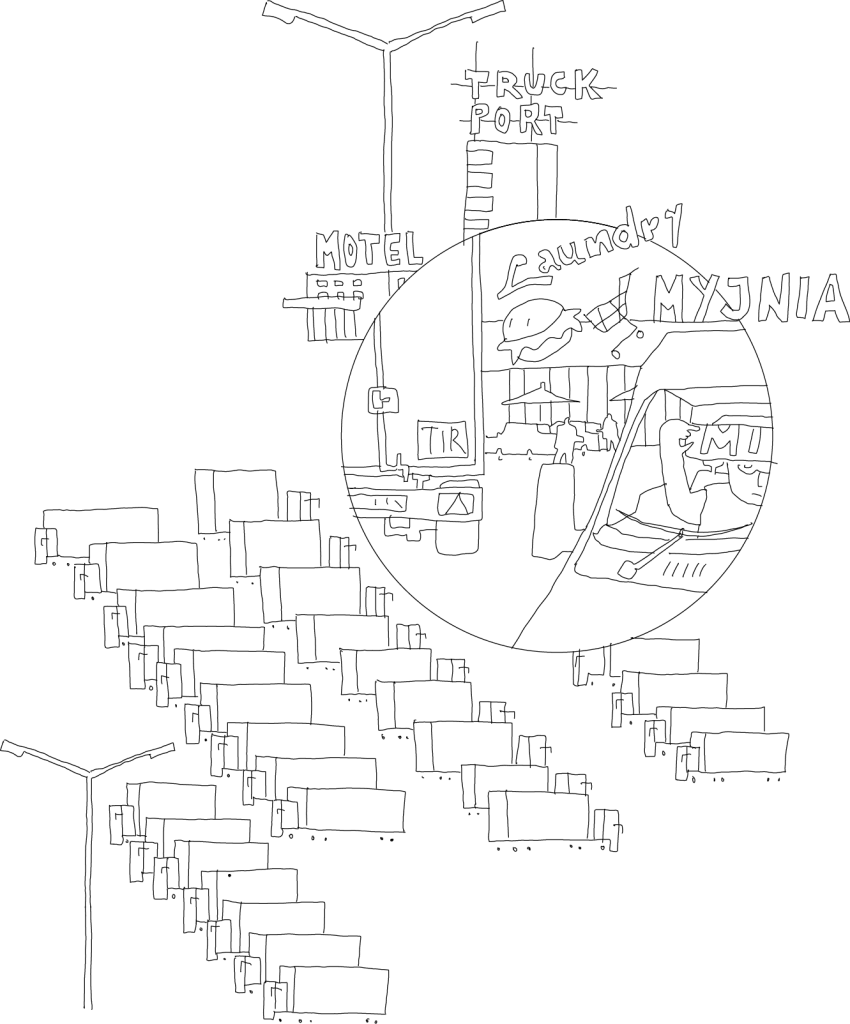

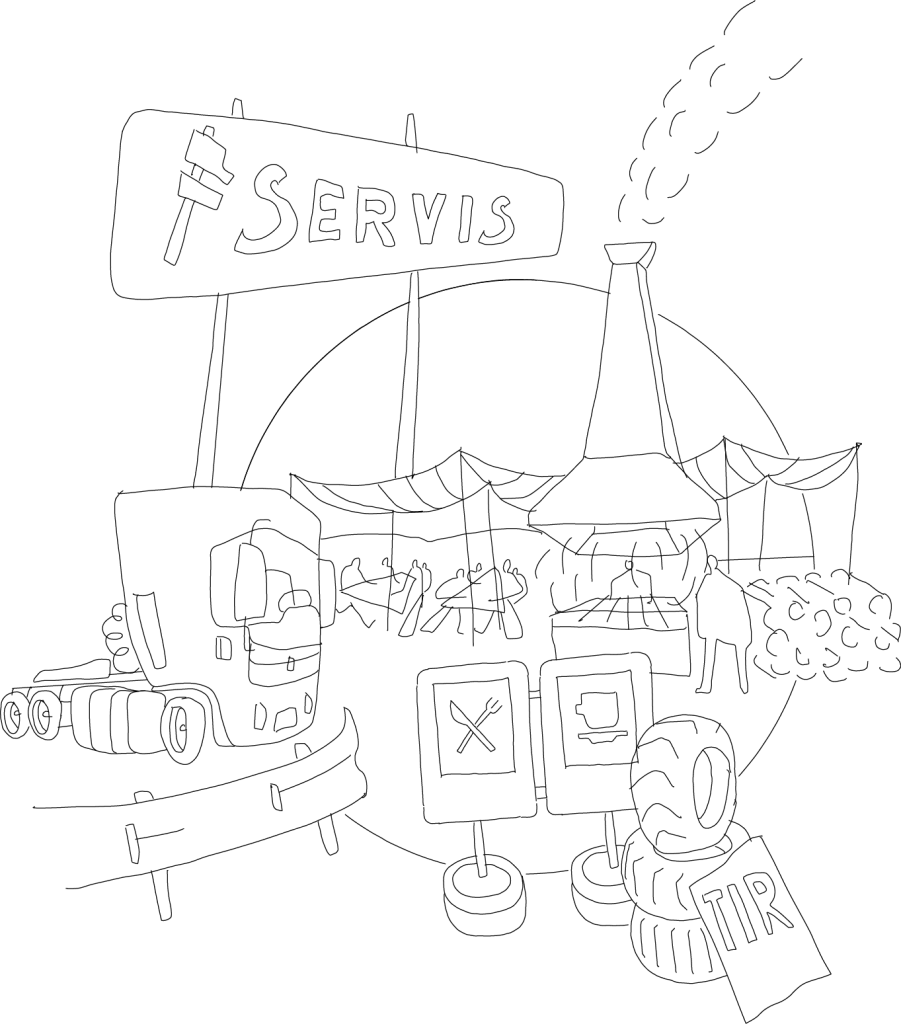

Of special interest to us had been the variety of highway service stations, and especially TIR stops, parking lots and service facilities specialized in HGV trucks and their drivers. While at newly constructed highway intersections national or private operator companies and professional gas stations use to offer modern and well-serviced parking facilities for HGV trucks at a predefined distance to each other, along the many other roads which are not yet modernized, the quality of built infrastructure and services, the social status of operators and visitors — but also the visual language, communicating towards the road — differs radically.

We stopped at super modern TIR stops with huge illuminated displays visible from a long distance, and with all kinds of facilities such as toilets, showers, laundry machines, special lounges for drivers, separated parking for small trucks, standard HGV trucks, and refrigerated vehicles, even offering power supply jackets for their cooling units, because otherwise these vehicles have their engines running throughout the night. Many of these modern stations, built or modernized with European Union infrastructure funds, might at first sight match Marc Augè’s perception of anthropological non-places, a-historic and highly regulated by predefined paths, regulations and barriers, and plenty of signs and billboards, control and surveillance technologies.

But by driving the roads and stopping at nodes, we at least attributed specific meanings to these places in the context of the following travelogue. And depending on the time spent there and the interest we showed, they were transformed into spaces of aesthetic, gastronomic or social experience. Here we either observed, directly encountered, or recorded the individual experience of others, owning these spaces, working there or passing by. By means of participant observation, conversations—and the method of live mapping — or online research for gaining further information, what had been non-places before for others, soon became deeply loaded with history and histories to us.

Although the combination of the geopolitical sphere, the specific landscape, the many signs and billboards, and the design of buildings and vehicles, and the service advertised there, are far from being neutral, these elements constitute an emotional semiotic appeal. And to be frank, we often enjoyed stopping out of pure aesthetic interest and anthropological curiosity, triggered by the attraction of this visual language.

For instance, we encountered such picturesque attractions as an old low-bed truck parked by the road carrying an even older municipal bus with signs on the windows advertising the services of a rather informal looking TIR stop on a vacant derelict industrial estate beyond it. Or we visited a graveled site by the roadside, where a local farmer was trying to capitalize on his piece of land, simply with a mobile toilet and three small containers for the security guard, a bar, and a prostitute offering her services.

E 461 (A5) Vienna – Brno / E 50 Brno – Katowice

Fast lanes

After packing our van with a selection of literature on theories and methods relevant to the topic and a few videos related to the issue, our toolbox and drawing boards for mapping exercises in the field, we already started from Vienna with some delay.

Passing by logistic clusters in the North of Vienna we headed for Brno. We were first stopped to purchase a road tax vignette for the Check republic. Instead of a generic modern gas station we chose a little shabby kiosk with a small café bar at the derelict Austrian-Czech border station, which is used mainly as truck parking today. Since the highway is not yet finished here, chances for streets side and border economies, like Casinos and brothels are still booming on the territory of the Czech Republic, addressing clients from Austria and people in transit.

From Brno to Katowice we changed to a super modern highway, offering no reason to stop, despite of going to a toilet or refilling the tank of car. We did not

even notice any traces of a border between the two nations. To us, Poland seemed to have exploited EU infrastructure funds most effectively: Especially the East West highways represented the most expensive motorways, we have seen so far, all providing crash barriers and huge noise reduction barriers, new service stations for cars and lorries. The land consumption for intersections was enormous, and several new and separated bridges were erected close to each. In addition to the overpass for the highway, there had been road-bridges for the state road, for farmers’ vehicles only, and for pedestrians. Poland also seemed to be the country with the highest number of special economic zones and speculative logistic facilities.

E 75 (A1) Warsaw – Katowice, km 439

TIR Stop

North of Katowice the modern highway changes into a Communist style four-lane street with traditional crossroads controlled by red lights. At the E75 between Katowice and Warsaw close to the village of Radmosko we passed a large compound located in the fields behind the street, which attracted our attention: Port Radomsko said a huge billboard on top of the main building and the parking lot was full with heavy trucks — many more than we have ever seen before and after at one single spot. We decided to make a U-turn at the next occasion and visited the site, which consisted of a main building with a restaurant, toilets and bathrooms, including also a shop for everyday needs of truck drivers (technical devices, hygienic articles and cheap food, but also gadgets to pimp up the drivers cabin) an ATM and currency exchange office, a second building with repair workshop specialized on trucks, and another accommodating a car wash, serving 4 lorries and trailers simultaneously, and a small boutique design hotel, addressing business people, where we checked in for the night.

We met the rather young owner and learned that he is the son of a surveying technician, who early learned about plans to build a special economic zone between the village and the highway. So he purchased a piece of land in between the projected development and the only access-street to the highway. Here he first opened a simple TIR parking and a car wash. In parallel to the construction of the special economic zone he gradually expanded his compound. Today the zone is partly finished and operating (with Italian Indesit as the biggest company producing tax free here and the Austrian-German Trenkwalder group, a leading Human Resources service provider in Central and Eastern Europe, subcontracting cheap labour force). And his “port” is able to offer parking facilities for up to 400 (!) heavy trucks. The only service obviously missing here is a gas station — but to get a licence for a gas station would presuppose to be politically much better connected to people in power than he will ever be, he said.

A5 / E 67 Marijampolė

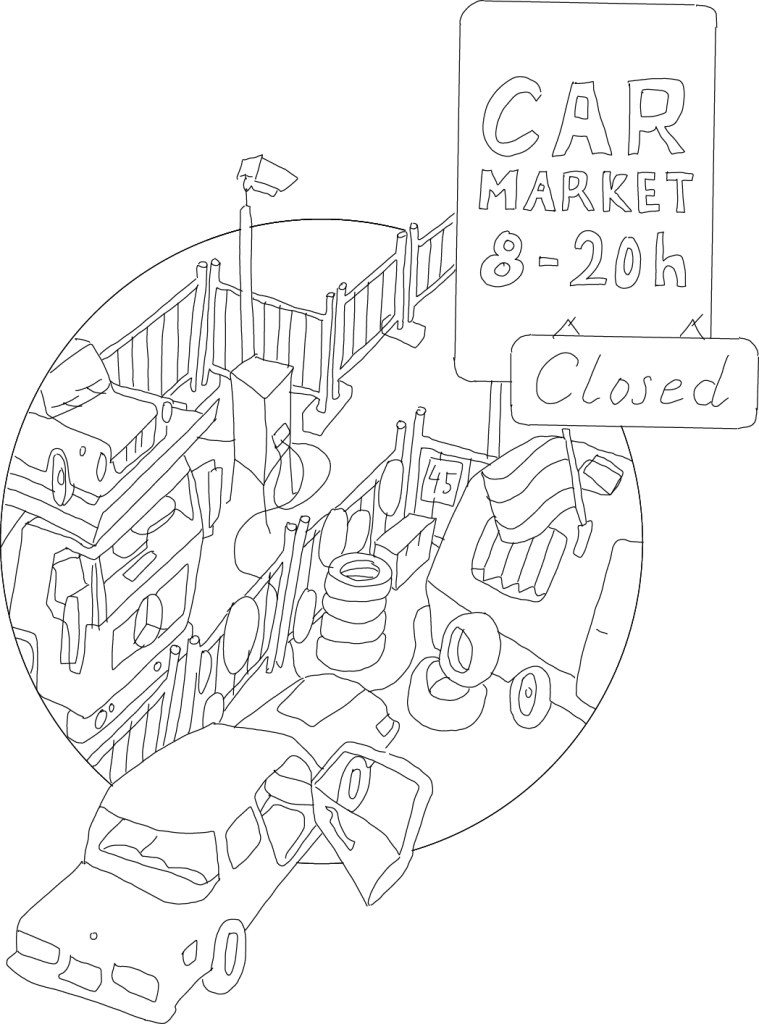

Second-hand car-markets

When approaching Lithuania, we had already been curious to see the second-hand car market of Marijampolje, famously described by Karl Schlögel in support of his thesis of a European East-West integration starting from below.12 The town is located very close to the Polish border at the crossroad of the E 67 Via Baltica connecting Warsaw with Helsinki and the E 28 connecting Kaliningrad with Minsk — and leading further to Moscow.

Starting immediately after the fall of the Iron Curtain, second-hand cars purchased and sometimes stolen in Western Europe, especially in Germany, were brought to a huge parking lot in front of a vacant factory. Some were sold directly from big car-trailers to the end users on site, others to vendors who transported them to post-Soviet states reaching from Kaliningrad and the Baltic to the Caspian Sea and even to Central Asia, also facilitating the Russian rail gauche starting here to forward vehicles in large numbers up to 100 cars by train.13 Originally this market happened only at one weekend a month, then expanded to happen every weekend, and finally became a permanent place for sale, managed by a private company which sub-rents parcels of land to other companies or individual vendors. During our second visit a year later, the parking lot was almost empty of cars. One of the last vendors recommended us to visit another market, specialised on transporter vans, like ours. Here we met an over-qualified guard, a computer programmer, he said, who spoke brilliant English and was happy to explain us the rules of the game and how changing of laws, exhaust emission regulations, and taxes had affected the demand for specific types of car. Big cars with huge cylinder capacity and fuel consumption, once so prestigious in Eastern Europe, had been literally driven out of the market, gradually displaced further to the East, first to Russia, then to Central Asia, while the demand for new economical cars with minimal exhaust values increased.

E 264 Tartu – Narva

Car accident

A car breakdown made us fall far behind our schedule: Originally we had planned to drive to Narva first to investigate the logistic areas on both sides of the Estonian-Russian border before arriving in Tallinn. But only 120 km before we expected to arrive we had a minor car breakdown. After calling the international emergency number we waited one and a half hour for the Estonian roadside assistance to send an ethnic Russian driver who did not even have a look for the engine or think about repairing the car, but instead loaded our huge van on his truck and drove us back to the official Ford service station in Tartu. This would have been a perfect situation for talking to him about his mobility and migration experience — if we would have been able to speak Russian.

In Tartu we had to stay overnight and some hours more to wait for our car to be repaired, therefore we had no more time to visit the Estonian-Russian border. By accident we checked in a popular tourist hotel in Tartu, which — surprisingly to us — also accommodated several German NATO officers, wearing combat uniforms for breakfast before training and supporting Estonian troops against potential Russian aggressions (this scary experience had been later re-enforced by detecting NATO warplanes at the airport and a NATO warship in the harbour of Tallinn, and meeting a convoy of NATO military vehicles at a border station between Estonia and Latvia).

E 267 / E 263 Tallinn

Evaluating preselected nodes

Our trip to Tallinn was purposefully scheduled to arrive in time for the EASA conference at Tallinn University14 which we saw as an opportunity to present the theoretical framework and methods developed in the course of our preceding art-based research projects, focusing on nodes of mobility and migration as well as the concept of our current project — and the interim experience made during this trip. Therefore over the course of the conference, we chose two afternoons to test our live-mapping techniques at a frequented area in front of the Russian market, to acquire information about the (ethnic Russian) market vendors’ experiences of mobility and migration and about the flow of goods, sold at this market. In contrast to our naive expectations, most of the cheap goods offered by the Russian vendors here had not been imported from Russia, rather from a market south of Warsaw, beside the route we drove before. We decided to visit this market upon the next occasion we came: It turned out to be the largest wholesale market for Asian products in Europe, run by Turkish, Vietnamese, and Chinese immigrants — and one of the most researched.

E 85 Vilnius – Ruse

Car breakdown

When driving down south from Tallinn towards Romania, we did not dare to drive the pan-European corridor 9 connecting Petersburg, Moscow, Kiev, Odessa, Chisinau, and Bucharest because of the fights in Eastern Ukraine. Instead we took the E85, which seemed to be a shortcut crossing the western part of Belarus and Ukraine.

While having no trouble in Belarus, the roads heading from North to South in Ukraine had been in such a bad condition that we had to drive extremely slowly and only the raised seat height of our van helped us identify the many craters and potholes of the streets. Nevertheless the longitudinal girder of our trailer broke. Luckily a worker of a former kolkhoz offered us help. We pulled the trailer to a big stable or workshop, where he welded some old metal pieces together to create a splint for stabilizing the girder. Again, this would have been a perfect situation for talking to him — if we would have been able to speak Ukraine. This time we lost only a few hours, but also lost significant time at the many borders between Lithuania and Belarus (EU-Border), Belarus and Ukraine (pro-Russian versus anti-Russian regimes), Ukraine and Romania (EU-Border), and Romania and Bulgaria (a bridge to be crossed with a road tax ticket only). Since our Ford Transit was registered as a truck, here we had been treated like truck drivers, and forced to fill out the same custom papers and pay fees. Because of our lack of language competence the border rituals only worked out thanks to the help of migrant workers and minivan drivers who returned from Germany.

Ruse

Border Town and Logistic Hub

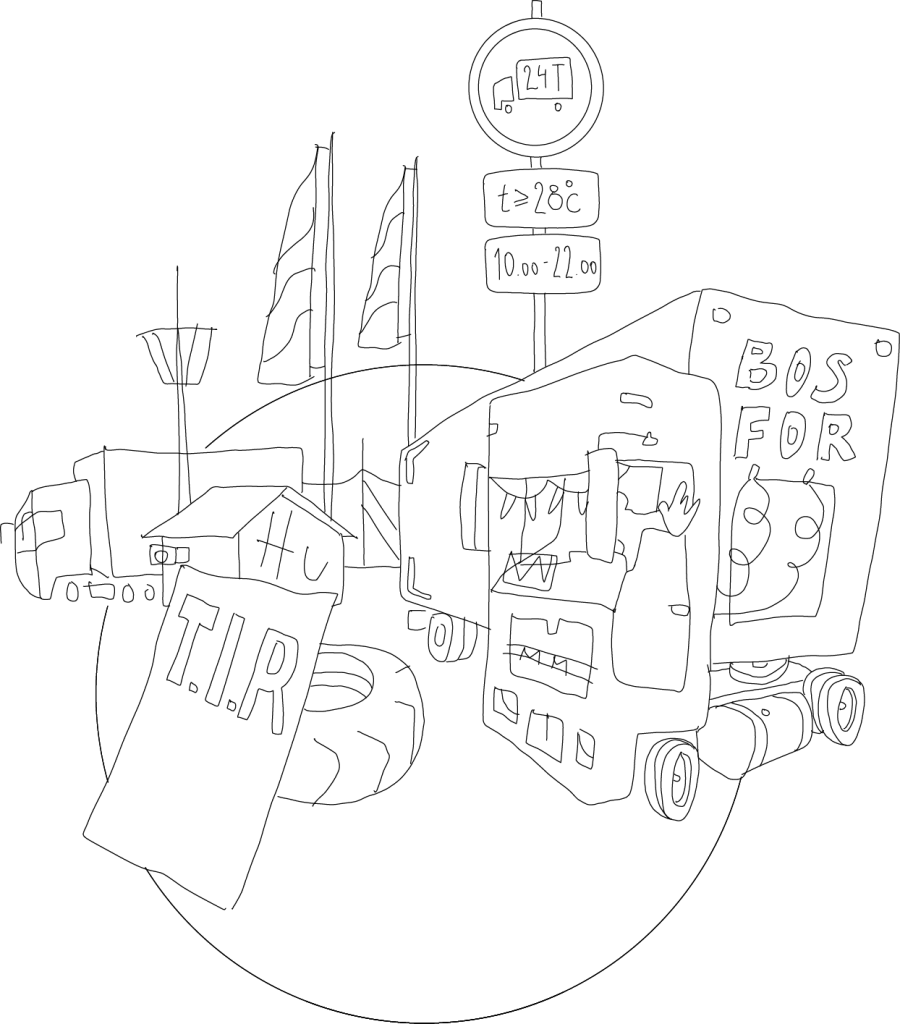

Here we met our Bulgarian research partner Emi Karaboeva who planned to investigate the networks of SOMAT (International Road Transport Corporation), the state monopolist in socialist Bulgaria, having thousands of heavy trucks crossing the borders of the Iron Curtain. Rouse has historically been an important node of transnational mobility due to the harbour at the riverbanks of the river Danube, a rail track, and most importantly, the road and rail bridge crossing the river Danube. From its construction in 1954 it remained the only rail and road connection between Bulgaria and Romania — until the opening of a second bridge in 2013 between Vidin and Calafat in the very West. Today two different pan-European transport corridors intersect: corridor 7, the Danube river, connecting the Black Sea and the Rhein-Main region in the heart of Germany, and corridor 9, connecting Helsinki and the Greek harbour city of Alexandroupolis. Furthermore all the transnational traffic volume between the Bulgarian-Turkish border and Bucharest necessarily passes by here. Therefore we looked for a former SOMAT service station here.

By accident the choice of the hotel had been rather productive: originally we had pre-reserved rooms only because of its specific location: easily accessible

from the highway bypass, at the southern margin of the Modernist city districts, and with a large parking lot to park the van and the trailer. After parking our van on the opposite street side of the hotel, we recognized the sign “BRANI 90 — First Private Autoline” mounted on top of a garage building. It turned out that this site was not only a hotel parking but a full service station for trucks and coaches, including a car wash, garages, a tire service, and a gasoline station. By accident we met the owner of the hotel at the check in. Actually, he was a former truck driver working for SOMAT during communist period of time, and, after leaving SOMAT, he argued, he became ‘the founder of the first private truck company in Bulgaria’.15 He seemed to be a perfect expert for our research issue. Therefore, we arranged a meeting to interview him the next day.

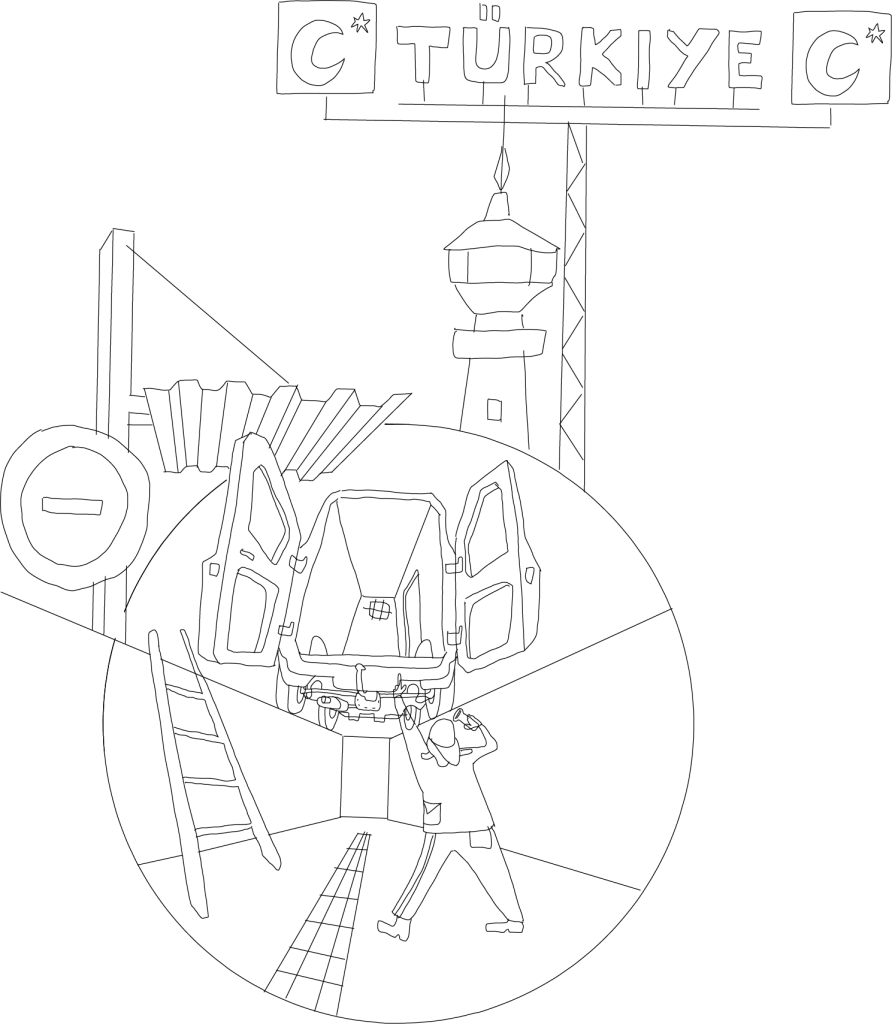

E 85 Ruse – Kapıkule

EU Border-Experience

From Rousse, we headed to the border between Bulgaria and Turkey, with the intention to cross it and to probably to see the parking lots and border economy at the Turkish side, and eventually to interview drivers over there. Since 2007 this station is one of the most important EU borders, officers accurately control both passports and approval certificates for cars (since cars might have been stolen and passengers might be wanted by the police in EU states).

After passing the control checks, we were told to drive our van into special hall, where they use to investigate cars for smuggling (drugs etc.). They searched inside the car and asked us whether we go to Turkey to look for work, they took our documents and left us waiting for an hour. It took us a while to identify the only person able to communicate in English: this woman did not allow us to cross the border and sent us back to Bulgaria instead, arguing that according to our papers, our van is registered a truck, not as a car, and we had illegally chosen the wrong queue. The whole situation was rather absurd and at the end we were not convinced that the formal reason for rejecting us, was the wrong queue. But lining up in the TIR truck line would have lasted half a day minimum. Therefore we never arrived in Turkey during this research trip.

E 80 Dimitrovgrad – Pazardzhik

TIR stop paradise

On the road to Pazardjik, we found several TIR stops of different character in a very short distance: One only offered a small booth, which was closed at the time we visited, with letters indicating that this is a terminal for Hungarian trucker drivers. But the place was dirty, without any security, no a proper ground for trucks or any additional facilities. The owner of the nearby restaurant — an ethnic Turkish Bulgarian told us that indeed Hungarian truckers stop there for signing their documents and sometimes also for eating in his restaurant, but also Turks.

If we want to see a “real” TIR terminal or parking, the owner of the restaurant recommended that we should drive back to visit a parking called “The Plane”, named after an old air-force plane exhibited aside the main street, to indicate the exit to reach a military airport nearby. This parking was paved with asphalt, clean, with visible security and an office, also offering rooms in a small motel. The trucks parking here had all been from Central European companies, Hungary, Czech Republic, and Poland, but most of the drivers were Turkish or Bulgarian.

The third stop was a guarded and fenced in paved parking, placed next to a gas station — with no staff visible. The main building was rather large, actually a prefab industrial structure covered with thick stone blocks, looking like a medieval castle, following the aesthetic pattern typical for many of the recently appearing casino centres. Inside was a rather dark and rustic but spacious restaurant, with a male cook, two waitresses, one of them the manager, and a prostitute. The place also looked clean, well organized, but not very populated. Large-scale flat-screens showed Turkish TV, additional services had been showers for drivers, and smaller separated rooms, closed off with curtains from the main hall.

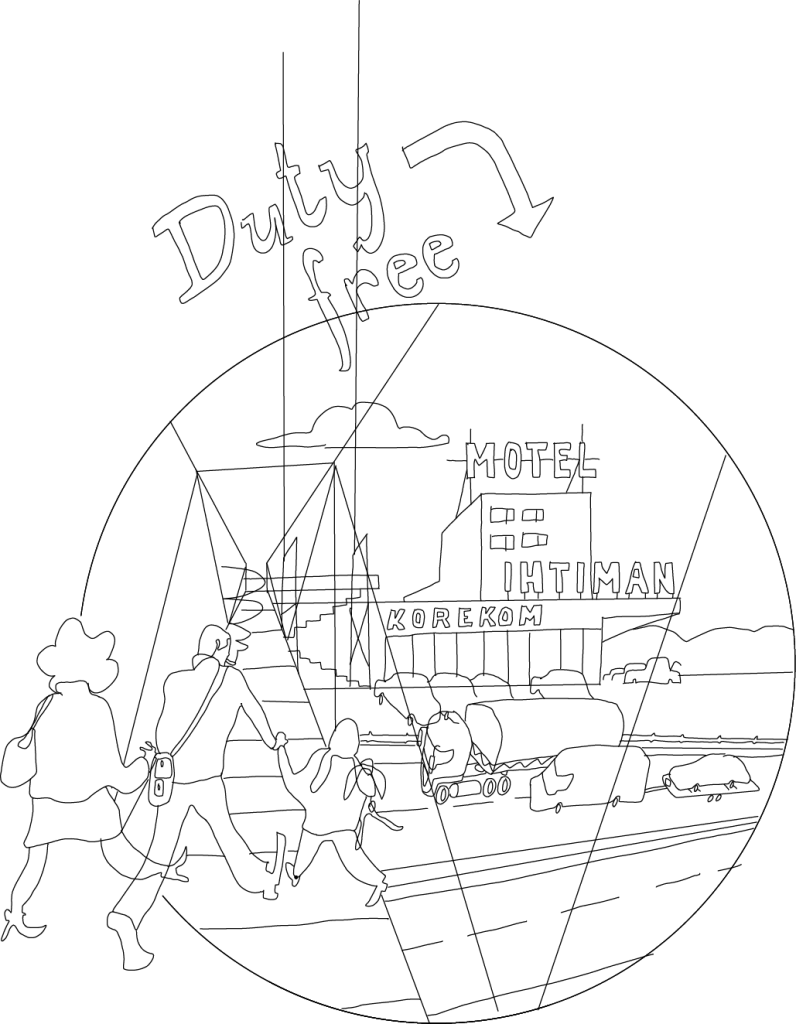

E 80 Pazardzhik – Sofia

Trakia Motorway: km 42

Motel Ihtiman is one the few large-scale motels built during the socialist period that survived the transition: it had been accessible from both sides of the highway by a passenger bridge crossing the highway (!). Originally there had been a gas station and a bar-restaurant on both sides, and the motel on the other side, consisting of a large parking lot for trucks, a smaller one for cars, a low building with a large bar-restaurant and a Korekom16 shop (today a large duty free shop and a designer outlet) facing the highway and a three-story hotel complex behind, all built in prefab modular metal construction. The motel then had offered rooms for the night and “for resting” (what the pricelist called a stay shorter than six hours). “At the end of the 1980s and the beginning of the 1990s, these buildings acquired something of a cult status, which had nothing to do with their perfect building

plan. Those who remember the end of the socialist period also remember the duty-free shops at the Iztok (…). Whether it was the Korekom, the motley trucks with their foreign lettering, or transit tourist and labour migrants, those places made it look like ‘you were not in Bulgaria,’ which was even visited and enjoyed by local families. As for taxi- and truck-drivers, they like to tell stories about the formative years of organized crime in Bulgaria, when these motels had been the stage for gambling, smuggling, prostitution and illegal foreign exchange (…).”17

E 75 / A 1 Nis – Belgrade – Subotica

Hotel, Motel, Grill

North of the Serbian city of Nis, the modern highway follows the path of the former Yugoslav “Autoput”, the famous “Highway of Brotherhood and Unity”, a core project of nation building under president Tito’s regime. During Socialism one of the most luxurious stops was also built here: 10 km north of Nis close to the intersection of two major pan-European corridors, on a hillside next to the highway a late modernist hotel/motel with a heated indoor pool and an outdoor pool of Olympic size, with an adjacent camping site was built, used both by transit tourists, business men, and — most recently — by (Turkish) truck drivers. Being an ambitious symbol of modernisation, and also well visited by local families, the hotel became a frivolous entertainment palace in the years after transition, before it got closed and vacant for several years.

Not far from here, some local entrepreneurs survived the modernisation of the highway by a rather strange tactic: exactly at the site of their famous and extremely popular grill palaces, located next to the old “Highway of Brotherhood and Unity”, the crash barriers at the side of the new one were either never built or dismantled later, to guarantee direct access from the highway to their parking lots — although from one direction only.

E 75 (M 5) Röszke – Budapest / E 60 Budapest – Vienna

Almost to the end

The closer we arrived towards our home the less attentive we had been for roadside economies. This lack of attention was due to the long journey before, that had been so exciting — and exhausting. But it was also supported by the fact that the entire section of the corridor between the Serbian-Hungarian border and Vienna is already developed into a modern highway not offering many attractions at first sight: One obvious exception is the logistic hub of BILK and the cluster of warehouses, hauling companies, HGV truck services and workshops at the A0 bypassing Budapest in the South. Here rail and road corridors intersect, connecting the harbours of Koper in Slovenia or Rijeka in Croatia with the road corridors to Greece and Turkey, to Romania and Ukraine, and via Bratislava to Warsaw or via Wien to Munich, etc.

Another place of interest had been the Hungarian-Austrian border-region of Nickelsdorf. But trying to make as many miles as possible, after leaving from or before returning to Vienna, attempting to get back to our homes and families in time, this area remained a blind spot in our research for a while. Since we felt we could do these investigations in between, we postponed them several times. And, exactly when the border-station had been over-run by thousands of migrants and refugees a day in the late August and September of 2015 we had already made an appointment for a workshop and installation in public space in Tallinn, 1’700 km away.18

Art based research, mobile ethnography, and the aesthetics of roads and roadside infrastructure

We are — of course — not alone with our fascination of the “road”: The aesthetics of roads and roadside infrastructure is reflected in myriads of novels, films, and works of fine art — ranging from road nightmares to heterotopic aspects of the road.19 And many artists had also been seriously interested in investigating global chains of goods and hubs of logistic industries.20 Our own practice was derived from a cluster of trans-disciplinary fields between art, arts-based research, urban and cultural studies and enjoys a significant impact of the “ethnographic turn in arts”21 within our work—also through collaborations we have conducted previously with activists, historians, anthropologists, and ethnographers. Hence, visual methods are not as exciting per se for us (see our own preceding works).22 The combination of (live) mental mapping, abstract cartography, and cartoons we apply in our project refers to the universal visual language developed by the Viennese social democrat philosopher and social economist Otto Neurath in collaboration with illustrator Gert Arntz already in the 1920s.23 These tools, originally developed to analyse and communicate socio-economic developments to non-experts, represent the basis for all icons and info-graphics, including modern traffic management systems.

In the 1960s the postmodern appreciation for the semiotic language of popular street architecture by artists like Ed Ruscha,24 and urban planners like Kevin Lynch25 and most importantly Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown26 had paved the way to also introduce photographic methods, mind mapping and elements from the popular language of comics including speech bubbles — to literally make objects speak. Given their capacity to be easily readable and include non-experts, they had also been adopted for critical urban studies as tools for both semiotic and socio-spatial analyses27 and for projecting visionary urban design and architecture28 — or for the improvement of community life in a neighbourhood.

While driving from node to node during our research trips we applied live mapping exercises in the very field of research, and pop up exhibitions of artworks of others, photos and drawings of ourselves — like those we use to illustrate this paper — at contact zones and social condensers to trigger further conversation. This allowed us to get close to the people and infrastructures that use and facilitate a range of mobilities, including shipping, working, trade, and migration. The size of our vehicle and trailer automatically predetermined the places where we parked or stayed overnight, at parking lots for lorries and TIR stops, protected areas for international truck drivers, where we were literally embedded and embodied in the social field of our research. But often we were identified as non-professionals or even absolute beginners, having a car not as heavily loaded as all the others, not knowing a thing about how to fill in papers and bribe border control staff or police officers. For us, being stopped in a check for illegal or criminal activity (by real or fake police officers), which would otherwise be an embarrassing interruption of a trip, became an exciting subfield of research. And even the seemingly endless time spent driving the pan-European corridors was not considered “dead time” in our minds but rather a productive period for re-discussing and re-evaluating interim research findings and for improving and preparing methods for conversation and elicitation to be applied at the next stop.

Above all, while we investigated how other people are “doing with space” at these nodes and what these spaces are doing with them, we became aware of how we ourselves are “doing with space.”

1. Homi Bhabha, ‘Unsatisfied: Notes on Vernacular Cosmopolitanism,’ in Text and Nation, ed. Laura Garcia-Morena and Peter C. Pfeifer (London: Camden House, 2001), 191—207.

2. Michel Lussault and Mathis Stock, ‘Doing with Space: Towards a Pragmatics of Space,’ Social Geography 5, no. 1 (2010): 12; Sarah Green, ‘Anthropological Knots,’ Hau: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 4 (3) (2014): 1—21; Tim Ingold, The Life of Lines (New York: Routledge, 2015).

3. Peter Merriman, Driving spaces: a cultural-historical geography of England’s M1 motorway (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007).

4. Samuel Austin, ‘Travels in Lounge Space: Placing the Contemporary British Motorway Service Area,’ PhD thesis at the Welsh School of Architecture, Cardiff University, 2011.

5. Nicky Gregson, Mobilities, ‘Mobilities, mobile work and habitation: truck drivers and the crisis in occupational auto-mobility in the UK,’ Mobilities (2018).

6. John Law, ‘Objects and Spaces,’ Theory, Culture and Society 19(2002): 91—105.

7. Julie Cidell, ‘Distribution Centers as Distributed Places: Mobility, Infrastructure and Truck Traffic,’ in Cargomobilities, ed. T. Birtchnell, S. Savitzky, and J. Urry (London: Routledge, 2015), 17—34.

8. Thomas Sieverts, Zwischenstadt. Zwischen Ort und Welt, Raum und Zeit, Stadt und Land (Braunschweig: Vieweg, 1997); Paul Knox, Metroburbia USA (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2008).

9. Bittner, et al.(eds.), Transit Spaces; Susanne Hauser, ‘Die Ästhetik der Agglomeration,’ in B1/A40: The Beauty of the Grand Road, ed. Markus Ambach Projekte et al. (Berlin: Jovis, 2010), 202—213.

10. Monica Büscher and John Urry, ‘Mobile Methods and the Empirical,’ European Journal of Social Theory 12 (February 2009): 99—116.

11. Further reading with evidence from case studies: Michael Zinganel and Michael Hieslmair (eds). Stop and Go — Nodes of Transformation and Transition. Publication Series of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna Vol. 23 (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019); about the exhibition: M. Zinganel and M. Hieslmair (eds), Road*Registers: Logbook of mobile worlds (Vienna: Tracing Spaces 2017), https://tracingspaces.net/road-registers/ and about methods applied: M. Zinganel and M. Hieslmair, ‘Stop and Go,’ JAR Journal of Artistic Research, Issue 14 (2017), https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/330596/330597

12. Karl Schlögel, Marjampole oder Europas Wiederkehr aus dem Geist der Städte (München: Hanser, 2005).

13. Wladimir Sgibnev and Andrey Vozyanov, ‘Assemblages of mobility: the marshrutkas of Central Asia,’ Central Asian Survey 35, no. 2 (2016): 276—291; 286.

14. The 13th EASA (European Association of Social Anthropologists) Biennial Conference took place in Tallinn University from July 31 to August 3, 2014. Our contribution had been published with other papers of our panel in: Judith Laister and Anna Lipphardt (Eds.), ‘Urban Place-making Between Art, Qualitative Research and Politics,’ Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, Volume 24, No. 2, 2015.

15. Bojidar B., interview by the authors (Ruse, August 8, 2014).

16. “Corecom” is an abbreviation for “Comptoir de représentation et de commerce”, but by Bulgarians the Cyrillic spelling “Korekom” was jestingly interpreted as korekten komunizăm, meaning “correct communism”.

17. Aneta Vassileva, ‘No Country for Old Motels,’ Списание Едно/ Edno Magazine (Summer 2011): 158—167.

18. But we later expanded and adapted our research to include the new nodes and modes of refugees’ and migrants’ mobilisation at the border station of Nickelsdorf, inter alias drawing a map of the reactivated border infrastructure based on conversations with Gerhard Zapfl, mayor of the border village, and even producing an animated graphic novel based on interviews with bus drivers: This animation had been shown inter alias at the exhibition ‘Unschärfen und weiße Flecken: Kartografische Annäherung an urbane Räume,’ kunsthaus muerz, Mürzzuschlag/Austria, April 4 — June 11, 2017; at the conference ‘Mobile Utopia: pasts, presents, futures’ at the Centre for Mobilities Research at Lancaster University, November 2 — 5, 2017; and at EASA 2018: Staying, Moving, Settling at Stockholm University, August 14 — 17, 2018. The English language version is accessible online: https://tracingspaces.net/bus-stop/

19. For mobility-related artworks, see: Julio Cortázar and Carol Dunlop, Autonauts of the Cosmoroute: A Timeless Voyage From Paris to Marseille, translated by Anne McLean (New York: Archipelago Books, 2007), and many more; see also: M. Zinganel and M. Hieslmair (eds), Road*Registers: Logbook of mobile worlds (Vienna: Tracing Spaces 2017): https://tracingspaces.net/road-registers/

20. About mobility-related research based art, see: Bill Roberts, ‘Production in View: Allan Sekula’s Fish Story and the Thawing of Postmodernism,’ Tate Papers, no. 18 (Autumn 2012); See also: Claire Bishop, ‘The Social Turn: Collaboration and its Discontents,’ Artforum (February 2006): 179—85; Lars Bang Larsen, ‘The Long Nineties,’ Frieze, no. 144 (January—February 2012): 92—95; Franke, Anselm (ed.) (2005) B-ZONE: Becoming Europe and beyond, Barcelona: Actar; and, for more details, Stefan Kaegi, ‘Cargo Sofia-X. A Bulgarian truck-ride through European cities,’ in Rimini Protokoll 2005-2007 http://www.rimini-protokoll.de/website/en/project/cargo-sofia-x

21. Kris Rutten, An van Dienderen and Ronald Soetaert, ‘Revisiting the ethnographic turn in contemporary art,’ Critical Arts: South-North Cultural and Media Studies 27, no. 5 (2013): 459—473.

22. Michael Zinganel and Michael Hieslmair, ‘Stopover: An excerpt from the network of actor-oriented mobility movements,’ in New Mobilities Regimes in Art and Social Science, ed. by Sven Kesselring, Gerlinde Vogl and Susanne Witzgall, 115—134 (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2013). See also: MHMZ at trackingspaces.net, [several texts], https://mhmz.at and https://tracingspaces.net/

23. Felix Keller, ‘Gesellschaft als Comic. Soziologie via Bilderzählung,’ in Wissen durch Bilder. Sachcomics als Medien von Bildung und Information, ed. by Urs Hangartner, Felix Keller and Dorothea Oechslin, 93—130 (Bielefeld: transcript, 2013). Angelique Gross, Die Bildpädagogik Otto Neuraths. Methodische Prinzipien der Darstellung von Wissen (Heidelberg: Springer 2015).

24. See the self-published artist’s books by Edward Ruscha, Twentysix Gasoline Stations (Los Angeles: Edward Ruscha, 1963) and Every Building on the Sunset Strip (Los Angeles: Ed Ruscha, 1966).

25. Kevin Lynch, The Image of the City (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1960).

26. Robert Venturi, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour, Learning from Las Vegas: The Forgotten Symbolism of Architectural Form (Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 1972).

27. Regina Bittner, Wilfried Hackenbroich and Kai Vöckler (eds.), Transiträume: Transit Spaces, Edition Bauhaus, vol. 19 (Berlin: Jovis, 2006).

28. James Corner, ‘The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention,’ In Mappings. Edited by Denis Cosgrove, 213—252 (London: Reaktion Books 1999).